Withholding Tax on Real Estate Sales in Florida: A Strategic Guide for Landlords Considering an Appeal

A real estate exit should be modeled as an integrated system, where withholding reflects broader gain character, NIIT exposure, and multi-year sequencing. This framework is especially important when analyzing withholding tax on real estate sales Florida investors encounter in cross-border or multi-entity structures.

High-income Florida real estate investors usually don’t think about “withholding” until a title agent tells them a meaningful percentage of the gross sales price is being sent to the IRS. In a large transaction, that can look like a seven-figure liquidity haircut on closing day—regardless of whether the seller has a low taxable gain, suspended losses, or a plan to defer recognition.

That moment is where two separate issues get conflated:

Florida has no state income tax, so there is no Florida income-tax withholding regime on real estate sales.

The withholding investors run into at closings is typically federal, and in most cases it is a FIRPTA (Foreign Investment in Real Property Tax Act) withholding requirement that applies when a seller is treated as a foreign person for U.S. tax purposes, or when ownership is structured in a way that causes foreign-person rules to attach.

For sophisticated landlords, the right question isn’t “How do we get the withholding removed?” It’s “What does this transaction do to our multi-year tax posture, and how do we keep liquidity, timing, and compliance aligned?”

We treat withholding tax on real estate sales Florida investors encounter as a planning signal: an indicator that the exit needs better sequencing, better documentation of taxpayer status, and a better integration of recapture, NIIT, entity structure, and reinvestment objectives.

Key Takeaways

The most common “withholding” at Florida closings is FIRPTA, which is a buyer-side obligation triggered by a seller’s foreign status (or foreign ownership in the structure), and it is based on amount realized, not net gain.

A successful “appeal” is generally a withholding certificate strategy: reducing withholding to better match projected tax by modeling the full exit-year stack (capital gain, recapture, NIIT, and other income).

Exit-year planning fails when it ignores depreciation recapture and unrecaptured §1250 gain, which can dominate the tax outcome even when headline appreciation looks modest.

NIIT is frequently the silent driver for high-income landlords; classification and participation decisions made years earlier can become binding at sale.

Entity and ownership design determine whether you can allocate, document, and time the sale cleanly—or whether withholding and reporting become a liquidity and negotiation problem at closing.

The best liquidity outcome is not always the lowest withholding; the objective is a coordinated, defensible plan that supports reinvestment, reserves, and multi-year efficiency.

We’ll review ownership and entity flow-through to see how gain character and withholding mechanics behave over a multi-year exit.

What “Withholding Tax” Means in Florida Real Estate Sales

When Florida sellers talk about “withholding tax,” they’re often describing one of three very different concepts:

For clarity, when we use the term “appeal” in this guide, we are referring to the formal process of requesting reduced withholding—most commonly through a withholding certificate—rather than disputing a tax assessment after the fact.

1) FIRPTA withholding (most common in practice)

When Florida sellers talk about “withholding tax,” they are typically referring to federal withholding under FIRPTA. In most cases, FIRPTA applies when a seller is treated as a foreign person for U.S. tax purposes, or when foreign ownership exists within the selling structure. Domestic U.S. sellers who properly document non-foreign status generally are not subject to FIRPTA withholding, but documentation failures can still trigger conservative handling at closing. Under current IRS guidance, the withholding rate is generally 15% of the amount realized, subject to exceptions and special rules. A commonly encountered exception is the buyer’s residence-use exception when the buyer is an individual acquiring the property as a residence and the amount realized is not more than $300,000, with an intent to meet the IRS occupancy standard during the first two years after transfer. Because the default calculation is gross-based, withholding can materially exceed the seller’s eventual income tax.

2) A “non-foreign” status certification (what prevents unnecessary withholding)

Many unnecessary withholding situations arise when the buyer or closing agent does not have timely documentation that the seller is not a foreign person. For U.S. persons and domestic entities, providing the proper certification can be the difference between no withholding and a large, avoidable cash holdback.

3) Confusion with state real estate withholding regimes (not Florida)

Some states impose nonresident real estate withholding. Florida’s no-state-income-tax environment means Florida doesn’t operate that type of income tax withholding system. The federal withholding issue therefore tends to be the real driver for Florida deals, particularly when sellers, beneficial owners, or upstream entities are foreign.

The practical takeaway: in Florida, a “withholding” conversation is usually an international-status and structure conversation first, and only then an income-tax computation conversation.

Why Sophisticated Landlords Encounter Over-Withholding

Even when FIRPTA clearly applies, high-net-worth landlords disproportionately experience over-withholding because statutory withholding is intentionally blunt. It generally does not consider:

Adjusted basis, depreciation schedules, and prior cost segregation

Suspended passive losses that may be released at disposition

Capital loss carryforwards, charitable planning, or other offset capacity

Multi-asset sequencing (selling multiple properties or businesses in the same year)

Special structures (partnerships, trusts, tiered LLCs, and mixed foreign/U.S. ownership)

In other words, statutory withholding is designed for collection certainty, not accuracy.

Where over-withholding becomes an operational risk

For sophisticated investors, the real cost of over-withholding is not emotional—it’s strategic:

Reduced liquidity for a replacement-property deposit or other redeployment timeline

Forced bridge financing (and interest carry) because capital was trapped

Weaker negotiation position in short sales or lender workouts (where every dollar of proceeds is contested)

Delayed redeployment into opportunities, especially in Florida markets where timing matters

A reactive “sell now, fix taxes later” posture that invites avoidable execution mistakes

Over-withholding is often the first visible symptom that exit planning started too late.

The Appeal Concept: Reducing or Eliminating Withholding

Most “appeals” in this context are not disputes. They are formal requests to reduce withholding to a more appropriate amount based on projected tax liability. Practically, that usually means pursuing a withholding certificate through the IRS (commonly via Form 8288-B for foreign sellers) and coordinating it with closing logistics.

What makes a withholding reduction defensible

A credible reduction request is built on a full-scope projection that ties together:

Transaction structure (asset sale vs entity interest, allocation, liabilities assumed)

Gain character (capital gain vs recapture/unrecaptured §1250)

Exit-year ordinary income (including business income, bonuses, distributions)

NIIT exposure based on passive/active status and participation

Existing tax attributes (suspended losses, carryforwards) and how they unwind at sale

This is why sophisticated investors should not treat withholding as paperwork handled by the title company. The withholding number is an output of a tax model, not a clerical default.

Execution mechanics that matter (because they change outcomes)

Competitor content repeatedly emphasizes forms and timing for a reason: the withholding regime is enforced through process.

Withholding is typically remitted using Forms 8288 and 8288-A at the transaction level.

A withholding certificate request (commonly Form 8288-B) is most effective when it is aligned with the closing timeline and the transaction’s final structure (including debt and seller credits).

Buyers and settlement agents tend to default to conservative positions because they can be exposed if withholding is handled incorrectly, so clean documentation is not optional if you want flexibility.

The strategic implication: you don’t “negotiate” withholding at the closing table. You earn optionality by preparing earlier.

Timing: the hidden determinant of success

Withholding reduction is most effective when it is addressed before closing. From a planning standpoint, we treat this as a sequencing decision:

If you need liquidity for reinvestment or debt payoff, you plan the withholding certificate as part of the transaction timeline.

If liquidity is not binding, you may accept withholding and focus on getting the tax result right and recovering excess via filing.

Either way, withholding strategy is a cash-management decision embedded inside a tax and legal structure decision.

Income Stacking and Exit-Year Sequencing

For high earners, the exit year is rarely neutral. Real estate gains stack on top of:

Professional or W-2 income

K-1 income from operating businesses

Portfolio income and dividends

Other property sales or business exits

This stacking can drive second-order effects that matter more than the gain itself.

Sequencing across tax years: what sophisticated sellers actually control

Most investors focus on “sell this year vs next year” as a binary choice. In practice, sequencing has more levers:

Close early vs late in the year to control whether other income events (bonuses, distributions, capital calls) land in the same year.

Stage multiple dispositions across two years rather than selling a portfolio in one compressed window.

Coordinate with business income variability (for example, harvesting a lower-income year in an operating business to absorb an exit-year gain stack).

Plan the timing of improvements and repairs when they meaningfully affect basis and documentation (especially after casualty-driven work), rather than letting the schedule be dictated by contractors alone.

Sequencing is not about a single “best” year. It’s about reducing the odds that one year becomes a tax and liquidity bottleneck.

Failure mode: optimizing the sale year and ignoring the “after year”

Exit-year planning often fails because it treats the sale year as the only year that matters. In reality, the year after sale is often where investors realize they traded long-term efficiency for short-term simplicity:

Basis reset and depreciation capacity on replacement assets may change

Passive loss “release” may not be as usable as expected if ordinary income is already high

Liquidity decisions made under withholding pressure can push investors into higher-cost financing structures

A forced redeployment timeline can weaken underwriting discipline on replacement assets

Sequencing should be evaluated as a two- to three-year arc, not a one-year event.

Multi-year scenario framing (how we avoid surprises)

A durable exit plan typically models at least three scenarios:

High ordinary-income year sale (business is strong, bonus/distributions high)

Moderate income year sale (more room for loss utilization and charitable design)

Compressed liquidity year sale (insurance, casualty, or lender events force a faster exit)

When the tax model is prepared in advance, “appeal” decisions become straightforward execution choices rather than emergency measures.

NIIT Exposure: Often the Silent Driver

For many Florida landlords, NIIT is the tax layer that makes an exit feel “more expensive than expected,” even when headline capital gains rates seem manageable. NIIT tends to surface in two ways: it can apply to rental income during the hold, and it can apply to gain at disposition.

Why NIIT hits Florida landlords harder in practice

Florida’s lack of state income tax can create a false sense that “real estate exits are lighter here.” In reality, the federal NIIT layer is indifferent to Florida residency, and it often becomes more visible precisely because there’s no state tax to blend into the overall burden.

For investors earning $250k+ annually, NIIT analysis is not academic. It frequently becomes a deciding factor in whether to:

Rebalance between passive rentals and operating businesses

Invest through structures that support active treatment

Delay or accelerate dispositions relative to other income events

Preserve an “operating profile” that is consistent year over year, rather than drifting into an investment profile that increases NIIT exposure

Classification and documentation: the long-tail risk

NIIT outcomes at sale are heavily influenced by decisions that were made years earlier:

Whether the rental activity was structured and managed to support active participation

Whether there is credible, contemporaneous documentation of participation

Whether there are multiple activities that can or cannot be grouped for participation analysis

A common failure mode is assuming “we’re active because we’re involved,” without the operational facts and records to support it when the exit-year tax return is built.

Second-order NIIT planning: what changes when there are multiple exits

NIIT becomes especially important when a sale year includes multiple liquidity events (a property sale plus a business distribution event, for example). In that environment, NIIT planning is less about “avoiding NIIT” and more about:

Controlling how much net investment income lands in the same year

Avoiding unforced errors in activity classification that convert what could have been an operating profile into an investment profile

Coordinating installment timing or other sequencing tools (when commercially feasible) to prevent a one-year NIIT spike

The NIIT question is rarely solved with a single tax move. It is solved with structural choices and sequencing discipline.

NIIT and withholding: why the projection must be realistic

When a withholding reduction request is supported by an exit-year tax estimate, NIIT cannot be treated as an afterthought. If NIIT is likely to apply and the projection ignores it, the model becomes optimistic in exactly the way that creates downstream problems: underpayment risk, estimated tax surprises, and friction with buyers and settlement agents who prefer conservative positions.

We’ll model how NIIT and passive vs active treatment layer onto recapture and capital gain in a Florida real estate exit across multiple tax years.

Depreciation Recapture and Unrecaptured §1250 Gain

Landlords who have held Florida rentals for a decade often underestimate how much of the exit tax is driven by depreciation history rather than pure appreciation. Two concepts typically dominate:

Depreciation recapture (in various forms depending on assets and depreciation method)

Unrecaptured §1250 gain, which applies to certain depreciation on real property and is taxed differently than long-term capital gain

Why the exit “feels wrong” without a recapture model

If you model exit tax as “sale price minus purchase price,” you miss the biggest basis driver: depreciation. The tax system gave deductions during the hold, and at exit it often recharacterizes a portion of the gain into buckets that do not enjoy the same treatment as long-term capital gain.

This is why withholding reduction requests that only speak to “capital gain” can be misleading. A defensible projection separates:

Appreciation-driven gain

Depreciation-driven gain character

The interaction with other income and NIIT

Unwind scenarios: when recapture becomes a constraint

Recapture is not just an exit-year rate issue. It becomes a strategic constraint in unwind scenarios such as:

Selling after heavy cost segregation, when accelerated depreciation increased near-term cash flow but also increased recapture complexity

Selling in a high ordinary-income year, when stacking makes the recapture component more painful

Selling after major casualty repairs or capital improvements, where basis and component treatment affects gain character

Selling into a buyer-driven price reduction (credits, repair escrows) that changes “amount realized” mechanics but not necessarily the underlying depreciation history

Sophisticated planning is not about avoiding recapture. It is about deciding when the recapture “payment” is acceptable relative to liquidity, reinvestment, and long-term portfolio objectives.

Multi-year view: recapture versus depreciation capacity on replacement assets

A subtle second-order effect is that a sale can reduce future depreciation capacity if replacement assets are acquired differently or in different markets. In Florida, where investors often rotate between short-term rentals, multifamily, and mixed-use properties, depreciation profiles can vary significantly. Coordinating the exit with the next acquisition is part of making recapture economically rational.

Where “appeal” strategy breaks if you don’t model character

Withholding certificates and reduced-withholding strategies are strongest when they align with how the sale will be reported. If the projection assumes mostly long-term capital gain but the real result contains significant recapture and §1250 character, the reduction becomes fragile. For high earners, that is the difference between a clean close and a year-end scramble to cover underpayments.

Cost Segregation as a Planning Tool, Not a Tactic

Cost segregation can be excellent planning—when it is evaluated across the entire holding period and exit. It is not inherently a “write-off,” and it should not be deployed without modeling what it does to the disposition profile.

How prior cost segregation changes the withholding conversation

When FIRPTA applies, withholding is based on gross proceeds, and a withholding certificate request requires an estimate of tax liability. Prior cost segregation affects that estimate because accelerated depreciation changes:

Adjusted basis (and therefore total gain)

The character of gain at exit

The audit sensitivity of the positions taken during the holding period

If your depreciation strategy created large early deductions, your exit-year model should anticipate the consequences rather than hoping the withholding certificate “fixes” liquidity.

Failure mode: optimizing Year 1 and creating an exit-year problem

The most common misuse we see is treating cost segregation as an isolated acquisition-year move. That can backfire when:

The investor plans to sell sooner than expected due to market shifts, insurance pressures, or family/business liquidity needs

The property’s operating profile changes (short-term rental conversions, material participation shifts)

The investor moves toward a portfolio sale strategy, creating multiple recapture events in one year

Cost segregation should be revisited whenever the expected holding period or exit strategy changes.

Practical refinement: use cost seg to support a lifecycle plan

The cost segregation question that matters most is not “Can we accelerate depreciation?” It’s “If we accelerate now, what is the likely unwind path, and do we have the cash discipline and exit timing to make the lifecycle economics work?” For Florida landlords, this often ties directly to insurance-driven timing risk and the probability of an earlier-than-expected disposition.

Entity Structure and Ownership Implications

Entity structure is where sophisticated Florida investors either gain flexibility—or lose it at the closing table.

Withholding triggers and mixed ownership

FIRPTA is most straightforward when the seller is a single foreign individual. It becomes operationally complex when ownership is layered:

Multi-member LLCs taxed as partnerships

Trust ownership with foreign grantor considerations

Tiered structures where a U.S. entity is owned by foreign persons

Joint ownership where one spouse or member is foreign and another is U.S.

In these cases, withholding may apply to the foreign portion, and allocation mechanics matter. The ability to document capital contributions, ownership percentages, and certifications becomes a practical requirement, not an administrative preference.

Flexibility at exit: allocations, special allocations, and what actually holds up

Investors often assume an operating agreement can “allocate the gain” to manage tax outcomes. At exit, flexibility is constrained by:

Economic substance and capital account rules

The reality of who contributed what, and when

Debt allocations and refinancing history

The buyer’s willingness to accommodate complex structures

If withholding is being reduced through a certificate strategy, the projection must match the structure that will actually be reported. A mismatch creates compliance and audit risk.

Second-order planning: entity decisions that change the unwind path

Entity design also affects unwind scenarios:

A portfolio recapitalization or partial sale may be easier in one structure than another

A sale of entity interests versus a sale of underlying property can change buyer appetite and tax character

A later estate plan (including step-up goals and control) may conflict with an exit-driven entity decision

The best structure is not the one that produces the lowest tax in one year. It is the one that preserves options across market cycles.

The non-foreign certification angle (why entity hygiene matters)

A frequent cause of avoidable withholding is simple: closing teams cannot get comfortable with seller status because entity documentation is messy. When an entity’s ownership, taxpayer identification, or signatory authority is unclear, conservative withholding becomes the default. Clean entity hygiene—updated operating agreements, clear beneficial ownership, and timely certifications—often has a direct liquidity impact.

Active vs Passive Treatment at Exit

Many landlords accept passive classification during the holding period because it “works.” At disposition, that classification can become the hinge point for NIIT and for how losses release and are used.

The exit-year binding effect

At exit, the tax return must answer questions that were easy to ignore during operations:

Was the activity passive or non-passive?

Were grouped activities in place, and was the grouping defensible?

Is there credible evidence of material participation where it matters?

If the investor is relying on an active profile to reduce NIIT exposure, the support needs to exist before the sale, not after.

Suspended passive losses: not a magic eraser

A common misconception is that suspended passive losses automatically “wipe out” exit tax. In reality:

Losses release upon a qualifying disposition, but how valuable they are depends on the year’s overall income stack.

They may offset gain, but they do not necessarily neutralize recapture in the way investors intuitively expect.

If multiple activities are disposed of, the sequencing and grouping history can change what releases and when.

For high-income investors, passive loss release is best treated as a planning input, not the plan.

Practical refinement: participation strategy should match the exit story

If the exit plan depends on an active narrative, operational behavior should match that story well before a disposition is on the calendar. That means management structure, decision authority, and time allocation should be aligned with the tax position you expect to take later.

Cash Flow vs Long-Term Tax Efficiency

Withholding makes cash flow visible. That visibility can lead investors to over-optimize for immediate liquidity.

When reducing withholding is strategically correct

Reducing withholding can be a strong move when:

You need predictable capital for replacement property deposits, debt paydowns, or portfolio rebalancing.

You’re coordinating multiple exits and want to avoid unnecessary financing costs.

The modeled tax liability is clearly below statutory withholding and the projection is defensible.

When “just reduce withholding” backfires

Liquidity-first decisions can create long-term inefficiency when:

The model is overly optimistic and underestimates recapture, NIIT, or other income stacking

The investor uses released funds for unrelated spending, creating an estimated tax problem later

The exit plan changes midstream (deal re-trades, repair credits, casualty events) and the tax profile shifts

In sophisticated planning, we treat withholding reduction as one component of a broader liquidity plan that includes reserves, estimated payments, and reinvestment cadence.

Cash discipline is part of the tax plan

A refined approach links withholding decisions to cash discipline: if withholding is reduced, we plan where that cash sits, what it is earmarked for, and what triggers a reserve adjustment. That is how you avoid trading a closing-day liquidity win for a year-end underpayment problem.

Retirement, RMDs, and Sale Timing

For many Florida landlords, the exit is not just a portfolio event. It’s a retirement event—either because the investor is reducing operational complexity or because RMDs and pension income are beginning to matter more.

Coordinating sale timing with retirement income layers

A large sale can interact with retirement inflows in ways that change the effective tax outcome:

Pension and portfolio income can push the exit into a higher overall marginal environment

RMDs can reduce flexibility by adding income that is difficult to defer

Multiple account distributions can land in the same year as a property sale if not sequenced intentionally

This is why “sell when the market is good” is incomplete advice. The better question is “sell when the market is good and the tax year is prepared to absorb the exit.”

Second-order planning: liquidity needs versus post-sale income design

Another failure mode is selling an income-producing property without a plan for post-sale cash flow. Investors may then rebuild income through less tax-efficient vehicles or force distributions that were not needed. Coordinating the sale with retirement income design helps keep the plan sustainable rather than reactive.

Multi-year retirement sequencing (where it becomes binding)

Exit sequencing often becomes more constrained around retirement transitions: an investor may be winding down an operating business (reducing ordinary income variability) at the same time a property sale creates a large gain. In that window, the best planning is typically built around predictable cash flow, predictable estimated payments, and a deliberate posture on how much income is “allowed” to stack in one year.

Asset-Based Planning vs Deduction-First Thinking

Withholding problems are often created by a deduction-first mindset. The investor optimized early-year deductions without integrating the full lifecycle of the asset.

Asset-based planning starts with different questions:

What is the intended hold period, and what could change it?

What does the exit-year tax stack look like under multiple scenarios?

Where are the “pressure points” (recapture, NIIT, liquidity, financing) likely to appear?

How does the next asset’s depreciation and cash flow profile interact with this exit?

When you plan at the asset level, withholding becomes a manageable execution detail, not a closing-day surprise.

Refinement: treat withholding as an execution checkpoint, not a tax strategy

Once the multi-year plan is set, withholding becomes a checkpoint that confirms whether documentation, entity hygiene, and timing are aligned. If withholding is unexpectedly triggered, we treat that as a diagnostic: something in status, structure, or process was not fully integrated.

Correcting Common Misuse and Oversights

Even sophisticated investors fall into predictable traps around withholding and exit planning:

Assuming FIRPTA applies (or doesn’t) without validating status and ownership. Many unnecessary withholdings come from missing or late certifications, while true FIRPTA exposures can hide in tiered ownership.

Modeling “capital gain” and ignoring gain character. Depreciation history and §1250 concepts need to be modeled, not guessed.

Treating NIIT as an afterthought. NIIT is often the marginal layer that changes the economics of selling in a high-income year.

Over-relying on suspended losses. Passive loss release is real, but its value depends on sequencing and classification.

Forgetting the buyer’s risk posture. Buyers and settlement agents can be liable for withholding errors, so they will default to conservative positions unless documentation is clean.

Treating the withholding certificate as a substitute for planning. A certificate can improve liquidity, but it does not change gain character, recapture mechanics, or NIIT classification.

The corrective pattern is consistent: tighten documentation early, model the full stack, and coordinate the transaction timeline with the broader income calendar.

We’ll run unwind scenarios around recapture, income compression, and deal timing so liquidity choices don’t weaken long-term efficiency.

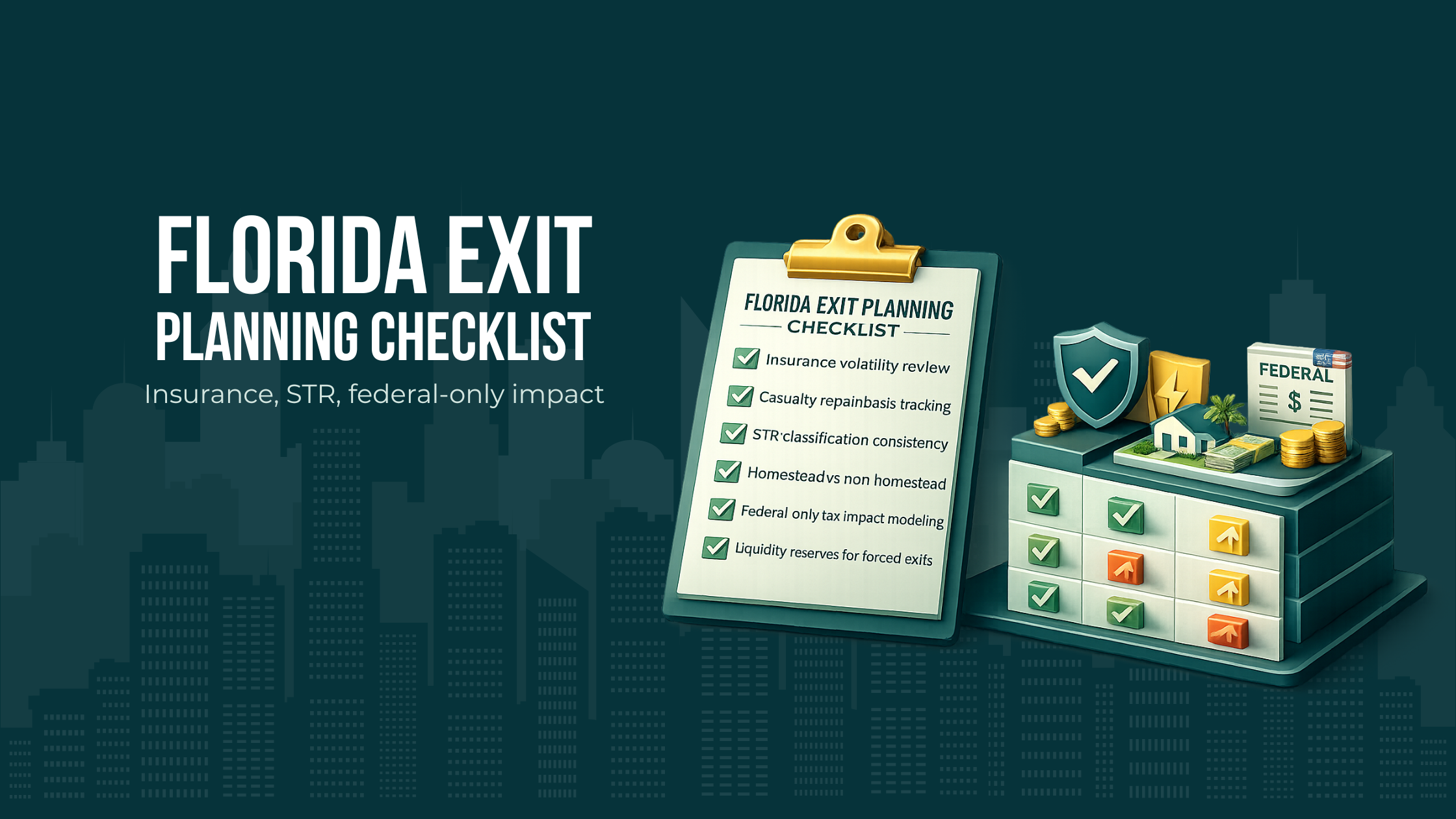

Florida-Specific Planning Considerations

Florida’s environment changes the analysis in ways that matter for high-income landlords.

Why federal planning carries more weight without state income tax

In a state with a material income tax, a seller might be balancing federal and state outcomes. In Florida, the federal system is the primary driver, which makes federal character rules—recapture, NIIT, and ordinary-income stacking—more consequential.

That also means investors can’t rely on “state savings” to soften the impact of a poorly timed exit. The sequencing discipline has to happen at the federal level.

Florida real estate concentration and exit/recapture exposure

Florida investors frequently hold concentrated positions in:

Coastal markets with higher volatility tied to insurance costs and storm risk

Short-term rental corridors where operating profiles and participation status can shift

Multifamily assets where cost segregation and improvements are common

Concentration increases the probability that multiple exits or restructures happen in the same window. That increases the importance of modeling recapture and NIIT as portfolio-level exposures, not property-level trivia.

In short-term rental markets, participation levels can fluctuate year to year, particularly when third-party managers are introduced or removed. That variability can affect whether rental income is treated as passive or active and, in turn, how NIIT applies at exit. For Florida landlords operating in STR corridors, consistency of operational structure matters as much as market performance.

Homestead vs non-homestead property tax implications for hold/sell decisions

While our focus here is income tax and withholding, property tax structure still affects exit decisions. Homestead dynamics can influence:

Whether a property is held as a true personal residence versus converted use

The economic cost of moving, consolidating, or reallocating property between personal and investment buckets

The timing pressure to sell or retain a non-homestead property when carrying costs rise

For landlords, the key is not the local rule itself. It’s how the property’s use classification interacts with the broader hold/sell decision and liquidity planning.

Insurance, casualty, and climate-driven planning risks

Florida’s casualty and insurance environment can force unplanned sales, especially after major storms or when underwriting changes materially. This creates distinct tax planning risks:

Holding period changes can collapse a multi-year plan into a short window

Repair cycles and casualty proceeds can complicate basis and disposition calculations

Liquidity reserves become more important so withholding does not force financing decisions under pressure

Exit timing may become correlated across multiple properties (for example, if a portfolio faces similar insurance constraints), increasing “stacking risk” in a single tax year

In Florida, we treat timing risk as a real planning input. A strong exit plan has contingency paths—not just a single “sell in Year X” assumption.

Conclusion

Withholding tax on real estate sales Florida investors encounter is usually not a Florida issue at all. It’s a federal withholding regime—most commonly FIRPTA—interacting with a complex ownership and exit profile. The right response is not simply to fight the withholding. The right response is to integrate withholding mechanics into a multi-year plan that models gain character, depreciation history, NIIT exposure, and the investor’s broader income calendar.

When we treat a disposition as a coordinated event—sequenced across years, aligned with retirement and business income, and supported by clean entity documentation—two things happen: liquidity becomes more predictable, and the tax result becomes more durable. That’s the standard sophisticated landlords should expect from an exit strategy: integration, not improvisation.

Bring your sale timeline and entity documents, and we’ll coordinate withholding strategy, sequencing, and retirement-year considerations.

Frequently asked questions

Should we delay closing into January to manage income stacking?

Sometimes. Delaying a closing can reduce compression in a high-income year, but only if the following year is structurally better. We look at the full stack: operating income variability, portfolio distributions, expected liquidity events, and how suspended losses will actually behave when released. Pushing a sale into January can help if it separates major income events. It can also backfire if the next year includes business growth, additional exits, or retirement distributions that eliminate the intended benefit. Timing should be modeled across at least two tax years, not decided by calendar convenience.

Is it ever smarter to accelerate a sale into the current year?

Yes, particularly when the current year offers capacity that the next year may not. For example, if ordinary income is temporarily lower, or if other income sources are expected to rise, accelerating a sale can preserve rate efficiency and reduce stacking pressure. We also consider capital markets risk, insurance renewals, and financing changes that could compress multiple exits into a future year. Acceleration is a strategic move when it reduces multi-year volatility, not simply when it feels administratively easier.

How do prior refinances affect depreciation recapture at exit?

Refinancing itself does not reset depreciation, but it often changes how investors perceive their basis and equity position. When leverage has increased over time, sellers may focus on loan payoff and cash-out history rather than accumulated depreciation. At exit, recapture is driven by depreciation taken, not by equity remaining. This disconnect can distort liquidity expectations. We evaluate the full depreciation ledger alongside debt history to avoid misjudging how much of the gain will be characterized differently from long-term capital gain.

What changes if we convert a rental to personal use before selling?

A conversion can change the character of future appreciation, but it does not eliminate prior depreciation history. Depreciation taken during rental years generally continues to influence gain character at disposition. The timing of conversion also affects which periods are treated as investment versus personal use. For Florida investors, where properties may move between short-term rental, long-term rental, and personal use, this analysis requires careful documentation. Conversion decisions should be coordinated with exit planning rather than treated as a late-stage tax maneuver.

How does installment sale treatment interact with recapture and NIIT?

Installment reporting can spread certain portions of gain across years, but it does not uniformly defer every component. Some elements, including depreciation-related gain, may not benefit from installment timing in the same way as appreciation-driven gain. Additionally, NIIT exposure may continue to apply depending on classification and overall income in each installment year. Installment structures can smooth cash flow and tax stacking, but they require a realistic projection of buyer credit risk, interest terms, and the investor’s broader income calendar.

What should multi-member LLC owners consider before listing a property?

Before going to market, multi-member owners should confirm capital accounts, ownership percentages, and any special allocation provisions are current and defensible. If foreign ownership exists anywhere in the chain, FIRPTA exposure needs to be identified early so documentation and withholding strategy can be addressed proactively. We also review how suspended losses and prior distributions have been tracked. Cleaning up entity records before listing often prevents conservative withholding decisions and avoids last-minute negotiation pressure.

How do Florida insurance and casualty dynamics influence exit timing?

Insurance availability and premium volatility in Florida can shift holding periods unexpectedly. A sharp increase in carrying costs or a post-storm repair cycle may compress what was intended to be a longer hold. Casualty events can also complicate basis calculations and interact with disposition timing. We treat these realities as planning inputs rather than external shocks. Building contingency timing into the exit model helps ensure that a forced or accelerated sale does not collide with other income events and create unnecessary stacking.

Does Florida’s lack of state income tax change how we think about exit sequencing?

Yes, because federal outcomes carry more weight when there is no state income tax to blend into the overall burden. In Florida, depreciation recapture, gain character, and NIIT layering become proportionally more significant. Without a state offset, a poorly sequenced federal exit can feel more concentrated. This makes multi-year coordination—especially across business income, retirement distributions, and portfolio exits—more important. The absence of state income tax simplifies one layer, but it heightens the need for precision at the federal level.