Florida Capital Gains Tax Planning for 2026: What High-Income Investors Actually Need to Think About

For Florida taxpayers, capital gains planning is often treated as a solved problem. There is no state income tax, long-term gains receive preferential federal treatment, and the assumption is that outcomes will naturally be efficient. In reality, Florida’s environment makes capital gains planning more consequential, not simpler.

When there is no state tax to absorb part of the burden, every capital gain sits directly on top of federal income, federal capital gains layers, and the Net Investment Income Tax. For high-income investors, business owners, and real estate operators, this means capital gains decisions rarely exist in isolation. They interact with ordinary income, depreciation history, participation status, entity structure, retirement distributions, and liquidity needs across decades.

The real risk is not paying tax. The risk is compressing income into the wrong years, locking in unfavorable character, or sacrificing long-term flexibility for short-term cash flow. Capital gains tax planning in 2026 should be approached as a sequencing and sustainability problem, not a rate comparison.

This article examines how federal capital gains actually function for Florida taxpayers, where sophisticated planning succeeds or fails, and how to think about exits and recognition events as part of a coordinated, multi-year strategy.

We’ll help you pressure-test how capital gains, depreciation recapture, and NIIT layer across years, not just in the exit year.

Key Takeaways

Florida’s lack of state income tax increases the importance of federal sequencing and structure.

Capital gains outcomes are driven by income stacking across years, not just holding period.

NIIT exposure is often structural and determined years before an exit occurs.

Real estate gains are recharacterized at sale, creating exit-year surprises if unmodeled.

Cost segregation and accelerated depreciation improve cash flow but reshape exit economics.

Long-term tax efficiency requires coordination with retirement income and liquidity planning.

See how entity structure and depreciation history change gain character and flexibility when assets are eventually sold.

Florida Capital Gains Tax: The Structural Reality

Florida does not impose a state income tax, which includes capital gains. That advantage is real, but it changes the planning calculus in ways that are often overlooked.

Without state tax, federal exposure becomes the dominant variable. For high earners, this means there is no offsetting deduction or rate arbitrage at the state level. Every additional dollar of gain increases federal adjusted gross income and may cascade into higher effective taxation through layering effects.

Florida taxpayers also tend to accumulate large, concentrated asset positions. Real estate portfolios, closely held businesses, and taxable investment accounts often represent decades of appreciation. When those assets are eventually sold, gains tend to cluster. The absence of state tax does nothing to mitigate the federal compression that occurs when multiple exits align.

Finally, Florida’s regulatory and economic environment encourages holding assets longer. Favorable property tax treatment for homestead properties, high in-migration, and strong rental demand all reinforce extended holding periods. Longer holds often mean larger embedded gains and more depreciation history, which magnifies exit-year complexity.

Federal Capital Gains Tax Framework in 2026

At the federal level, capital gains are divided into short-term and long-term categories. Short-term gains are taxed as ordinary income. Long-term gains benefit from preferential rate treatment.

For high-income taxpayers, the distinction between short- and long-term is only the first layer. Gains stack on top of other income, including:

Business or professional income

Rental income and passive activity flows

Portfolio dividends and interest

Retirement distributions and pensions

Once income crosses certain thresholds, the Net Investment Income Tax applies to many forms of investment income, including capital gains. NIIT does not replace capital gains tax; it layers on top of it.

The key planning insight is that capital gains do not have a fixed cost. Their effective tax rate depends on what else is happening in the same year and surrounding years.

Income Stacking and Multi-Year Sequencing

Income stacking is the mechanism through which otherwise favorable gains become inefficient. Gains recognized in years with elevated ordinary income often push taxpayers into higher effective layers, while the same gains recognized in lower-income years may be taxed more favorably.

Sophisticated planning treats capital gains as movable pieces within a broader income timeline. This includes evaluating:

Whether exits can be staggered across multiple tax years

How gains interact with variable business income

Whether certain years present natural “valleys” in income

How planned deductions or losses change the stacking order

Sequencing is especially important for Florida taxpayers transitioning out of active businesses or real estate portfolios. The years immediately before and after retirement often present opportunities to recognize gains more efficiently if planned in advance.

Without sequencing, gains default into the highest-income years by coincidence rather than design.

NIIT Exposure and Structural Control

The Net Investment Income Tax is often treated as unavoidable for high earners. In practice, exposure is frequently determined by structure and classification rather than income alone.

NIIT generally applies to capital gains, portfolio income, and passive activity income once modified adjusted gross income exceeds applicable thresholds. It does not apply uniformly to all income sources.

For real estate investors and business owners, NIIT exposure is influenced by:

Whether activities are classified as active or passive

How income flows through entities

Whether income is treated as investment or operating income

These determinations are rarely made in the exit year. They are the product of years of participation, documentation, and structural choices. A taxpayer who has consistently treated activities as passive cannot simply elect active treatment at sale to avoid NIIT.

NIIT planning therefore belongs in the design phase, not the unwind phase. Once gains are realized, exposure is largely locked in.

Real Estate Exits: Depreciation Recapture and Unrecaptured §1250 Gain

Real estate gains are frequently misunderstood as a single bucket taxed at long-term capital gains rates. In reality, gains are decomposed at sale into multiple components.

A portion of the gain reflects appreciation beyond original cost. Another portion reflects prior depreciation deductions. These components are taxed differently, with depreciation-related gain often subject to less favorable treatment.

For long-held Florida properties, depreciation recapture and unrecaptured §1250 gain can represent a substantial share of total gain. This is particularly true for assets that have undergone cost segregation or bonus depreciation.

The failure mode is not depreciation itself. The failure is accelerating depreciation without modeling how it will be unwound. Investors may optimize cash flow for years only to discover that exit-year taxation is higher and less flexible than anticipated.

Effective exit planning evaluates not just sale price, but gain character, timing, and interaction with other income in the sale year.

Cost Segregation as a Planning Tool, Not a Tactic

Cost segregation accelerates depreciation by reclassifying components of a property into shorter recovery periods. When applied appropriately, it improves near-term cash flow and increases reinvestment capacity.

However, cost segregation is not free. Accelerated depreciation increases the portion of gain subject to recapture or recharacterization at sale. For high-income investors, this often means that exit-year income becomes more heavily weighted toward less favorable layers.

The strategic question is not whether cost segregation “works,” but whether it aligns with the expected holding period, exit strategy, and income profile. In some cases, accelerating deductions during high-income operating years is optimal. In others, restraint preserves future flexibility.

Cost segregation delivers the best results when coordinated with long-term exit modeling rather than applied uniformly across every acquisition.

Entity and Ownership Structure Implications

Entity and ownership structure determine how gains are allocated, who recognizes them, and what flexibility exists at exit.

Partnerships, limited liability companies, S corporations, trusts, and individual ownership all impose different constraints. These structures affect:

Ability to stagger exits among owners

Allocation of gain character

Interaction with NIIT

Options for partial sales or redemptions

Once assets appreciate significantly, restructuring becomes difficult or impractical. Transfer taxes, built-in gains, and governance limitations can eliminate flexibility precisely when it is most valuable.

Sophisticated capital gains planning aligns entity structure with anticipated exit paths early, not as an afterthought.

Active vs Passive Treatment at Exit

Activity classification is often treated as an annual compliance issue. At exit, it becomes a binding determinant of tax cost.

Passive treatment exposes gains and depreciation-related income to NIIT and limits offset opportunities. Active treatment may reduce NIIT exposure but requires consistent participation and documentation over time.

Critically, status at exit reflects historical facts. Taxpayers cannot retroactively convert passive activity into active income in the year of sale. Years of reporting behavior matter.

This makes activity classification a long-term planning decision rather than a tactical one.

Cash Flow vs Long-Term Tax Efficiency

Many tax strategies optimize short-term cash flow while degrading long-term efficiency. Accelerated depreciation, aggressive deduction strategies, and income deferral can all improve near-term results while increasing future tax friction.

For Florida taxpayers with strong cash flow, the temptation is to maximize deductions without regard to unwind costs. Over time, this can lead to:

Heavily front-loaded depreciation

Large recapture exposure

Reduced flexibility at exit

Higher effective lifetime tax rates

Long-term efficiency favors balance. The goal is not minimizing tax in any single year, but smoothing outcomes across decades.

Retirement, RMDs, and Capital Gains Coordination

Capital gains planning does not end when active income declines. Retirement introduces new stacking dynamics that can materially affect outcomes.

Required minimum distributions, pensions, and portfolio withdrawals can crowd future tax years. Gains recognized later in life may stack on top of mandatory income, increasing effective taxation.

Strategic planning evaluates whether major exits should occur before, during, or after retirement transitions. It also considers how capital gains interact with retirement account strategies, income smoothing, and liquidity needs.

For many Florida taxpayers, peak asset values coincide with retirement. Without coordination, this convergence can produce avoidable compression.

Asset-Based Planning vs Deduction-First Thinking

Deduction-first planning focuses on annual tax reduction. Asset-based planning starts with the end in mind.

Asset-based planning asks:

Which assets will eventually be sold?

How will gains be characterized?

What years offer the most flexibility?

Where does recharacterization risk reside?

Deductions still matter, but they are evaluated based on how they change future options. This shift in perspective often leads to more durable outcomes.

Correcting Common Misuse and Oversights

Even sophisticated taxpayers fall into predictable traps:

Assuming all long-term gains are inherently efficient

Treating NIIT as an unavoidable surcharge

Overusing cost segregation without exit modeling

Ignoring entity rigidity until a sale is imminent

Optimizing deductions without regard to gain character

These missteps rarely cause immediate harm. Their impact emerges over time, when flexibility is lost and tax cost becomes unavoidable.

Corrective planning is about restraint and foresight, not abandoning effective tools.

We evaluate whether current cost segregation, participation status, and income stacking still hold up under an exit-year scenario.

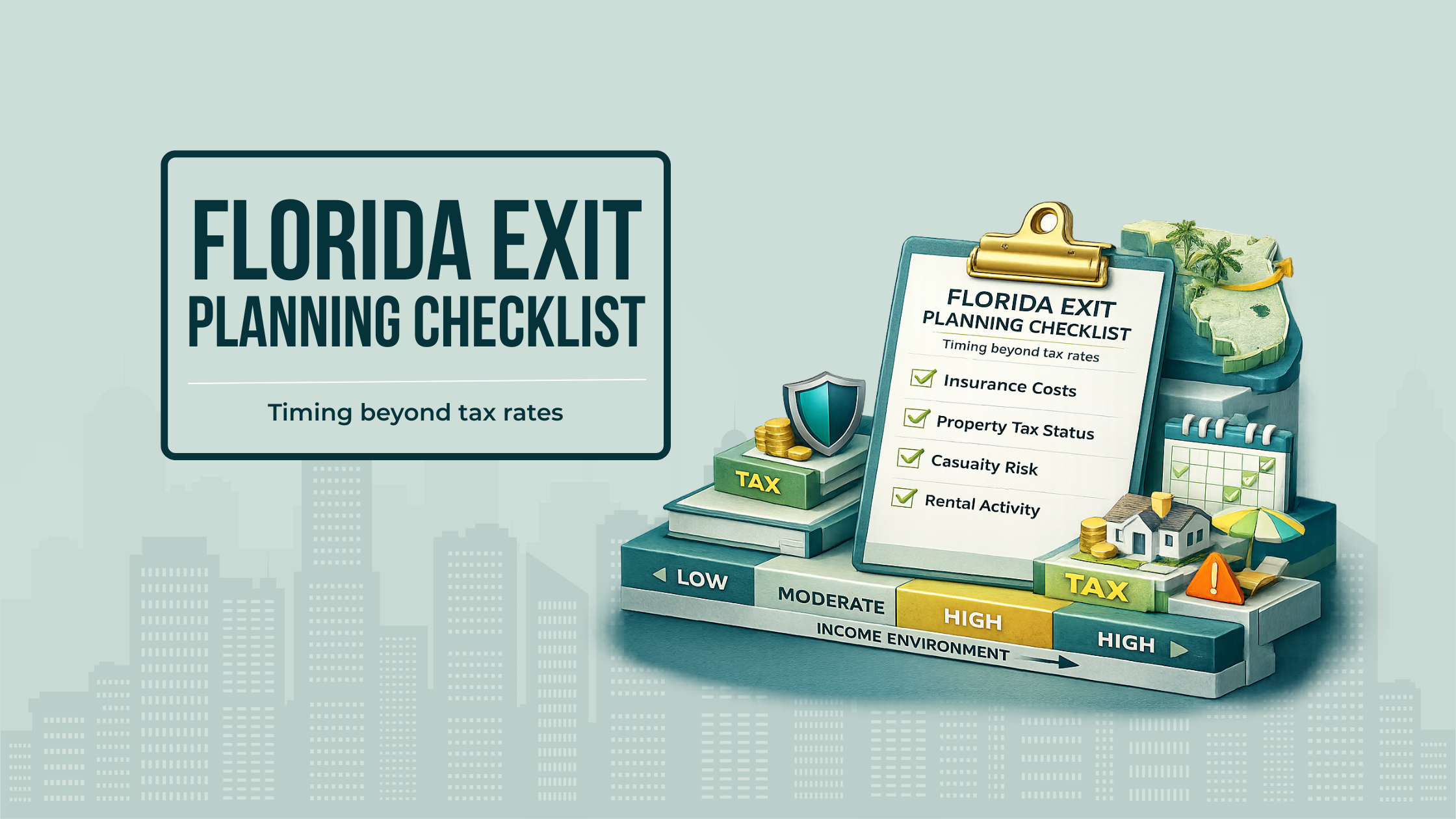

Florida-Specific Planning Considerations

Florida’s environment amplifies both opportunity and risk.

Without state income tax, federal exposure dominates outcomes. Real estate concentration increases depreciation recapture risk. Property tax distinctions between homestead and non-homestead properties influence hold-versus-sell decisions.

Insurance costs, casualty exposure, and climate risk also affect timing. Some investors choose to exit earlier or maintain higher liquidity reserves, which changes the optimal tax strategy.

Florida planning rewards nuance. Generic capital gains strategies often fail to account for these dynamics.

Conclusion

Florida capital gains tax planning in 2026 is not about chasing preferential rates. It is about sequencing income, structuring ownership, and anticipating how today’s decisions shape future exits.

When planning is fragmented, gains become unpredictable and expensive. When planning is integrated, capital gains become manageable components of a broader, multi-year strategy.

The difference is not complexity. It is coordination.

We design capital gains strategies that account for depreciation recapture, §1250 exposure, and entity constraints before liquidity events occur.

FAQs: Capital Gains Tax in Florida (2025)

How do we decide the “right” year to recognize a large capital gain?

The right year is rarely determined by the gain itself. It depends on what else is stacking in that year and what could be shifted before or after. Business income volatility, planned asset sales, depreciation runoff, and anticipated retirement income all matter. For Florida taxpayers, the absence of state tax means federal layering carries full weight. We often evaluate multiple recognition years side by side to identify where gains land most efficiently across ordinary income, capital gains layers, and NIIT exposure rather than defaulting to the earliest or most convenient year.

Is spreading gains across years always better than a single exit year?

Not always. Spreading gains can reduce compression, but it can also create inefficiencies if it pushes income into years with unfavorable stacking or eliminates opportunities to offset gain character. In some cases, concentrating gains in a deliberately chosen year produces a better lifetime outcome than smoothing them mechanically. Sequencing decisions should be based on how gain character, NIIT exposure, and other income sources interact over time, not on a general preference for spreading income.

How much should depreciation recapture influence the decision to sell a property?

Depreciation recapture often changes the economics of a sale more than expected. It increases the portion of gain taxed outside preferential capital gains layers and can materially raise effective tax cost in high-income years. The influence depends on how much depreciation has been taken, whether cost segregation was used, and what other income is present in the sale year. Recapture should be modeled explicitly as part of exit planning rather than treated as a secondary consideration.

Can earlier depreciation strategies make a future exit less flexible?

Yes. Accelerated depreciation improves near-term cash flow but can reduce flexibility later by increasing recharacterized gain at sale. This matters when multiple assets are sold in close proximity or when retirement income begins stacking in later years. Once depreciation has been claimed, unwind options are limited. This is why depreciation strategies work best when aligned with expected holding periods, exit timing, and long-term income plans rather than applied uniformly.

How does entity or ownership structure affect capital gains planning years down the line?

Entity structure determines how gains are allocated, whether partial exits are possible, and how much control exists over timing. Partnerships and multi-owner entities can limit flexibility once appreciation is substantial. Some structures make it difficult to stagger exits or shift recognition among owners. These constraints often surface only at sale, when restructuring is costly or impractical. Capital gains planning benefits from aligning ownership structure with anticipated exit paths well before liquidity events arise.

Why does passive vs active treatment matter more at exit than during operations?

During operations, passive classification often shows up as a limitation on loss usage. At exit, it affects whether gains and depreciation-related income are exposed to NIIT. Participation status reflects years of facts and reporting, not an election made at sale. A taxpayer who has consistently treated activities as passive may find exit-year exposure locked in. This makes participation planning a long-term decision rather than an annual compliance choice.

How does Florida’s no state income tax change capital gains strategy in practice?

Without state income tax, federal outcomes drive the entire result. There is no state-level deduction to soften compression in high-income years. Florida’s heavy real estate concentration, property tax distinctions between homestead and non-homestead properties, and elevated insurance and casualty risk can all influence hold-versus-sell decisions. These factors often affect timing and liquidity needs, which in turn shape when and how gains should be recognized for long-term efficiency.