Capital Gains Real Estate Tax Florida: Landlord Requirements and Multi-Year Exit Planning Framework

Florida landlords usually don’t lose money because their advisors missed a deduction. They lose money because the exit wasn’t designed.

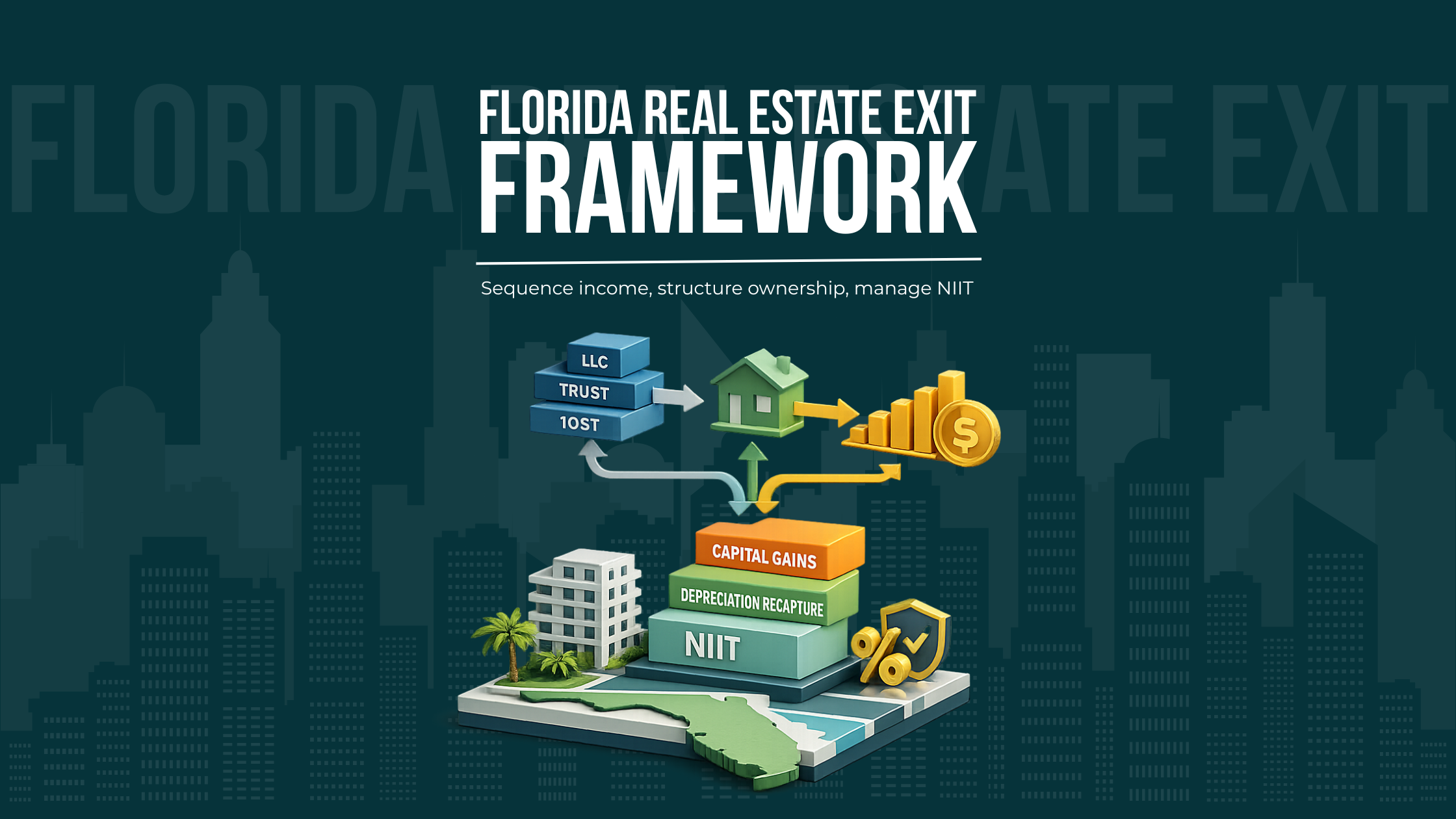

In Florida’s no-state-income-tax environment, there’s no state bracket to “manage around.” That sounds simple, but it raises the stakes: federal long-term capital gain brackets, depreciation-related gain (including unrecaptured §1250 gain), the 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT), passive activity limitations, and the timing interaction with everything else you earn. When the sale hits in the same year as peak business income, bonuses, large K-1 allocations, or a retirement-income inflection point, the result is often a concentrated, peak-rate event that also wastes planning assets (suspended losses, bracket capacity, charitable capacity, and sometimes even exchange flexibility).

The strategic question is not “What’s the capital gains rate in Florida?” Florida is the easy part. The real question is how to sequence income, structure ownership, and choose an exit path that holds up over multiple years, under real-world constraints (insurance volatility, casualty risk, partner misalignment, and capital reallocation pressure).

Key takeaways

Treat the sale year as a designed outcome, not a reporting year. The win is controlling what else is in the income stack when you exit, not debating a single capital gains rate.

NIIT is frequently the swing factor for Florida landlords. Whether a rental is passive vs nonpassive, and how it’s held, can change whether the gain is pulled into the NIIT base.

Depreciation is a timing tool with an unwind. Cost segregation can improve interim cash flow, but it can also increase ordinary-recapture exposure (for §1245 components) and expand the unrecaptured §1250 bucket at exit.

Entity and ownership structure are exit levers. Partnerships, S corporations, trusts, and multi-owner arrangements behave differently for allocations, suspended losses, and NIIT outcomes; structure determines flexibility when a buyer shows up.

Passive losses only matter when you can use them. A large suspended-loss position is not “savings” unless it’s released in the right year and matched to the right kind of income.

Florida-specific risks influence timing more than most models assume. Insurance and casualty risk can force earlier sales or accelerate capex, which changes holding-period assumptions and exit sequencing.

We’ll pressure-test recognition timing across exchange and installment options so the sale-year stack stays intentional.

What Florida landlords are actually taxed on when they sell

A Florida landlord’s sale typically creates several federal layers that behave differently and respond to different levers:

Capital gain on appreciation (generally long-term if held more than one year).

Depreciation-related gain, including:

Unrecaptured §1250 gain (the portion of gain attributable to depreciation on real property), and

Potential ordinary income recapture for certain reclassified components (common when cost segregation carved out §1245 property).

NIIT layering (3.8%) if your modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) is above the NIIT threshold and the gain is treated as net investment income.

Investors often talk about “the capital gains rate” as if it’s a single number. Real estate sales are rarely single-number events. A disciplined plan starts by modeling the buckets and then deciding which levers matter: timing, activity classification, structure, reinvestment path, and how aggressively you’ve accelerated depreciation.

A second-order effect many high-income investors underestimate is estimated tax management. Large, lumpy gains can create underpayment penalties if you treat the sale like a year-end surprise rather than a planned liquidity event with quarterly cadence.

The “requirements” Florida landlords must meet for long-term capital gain treatment

The landlord “requirements” are federal, not Florida, and they determine whether the rest of the strategy applies.

Holding period: the 12+ month gate

Long-term treatment generally requires more than one year of holding. If you sell at or before one year, the gain is typically short-term and taxed at ordinary income rates (and may still be NIIT-exposed). For investors who refinance, improve, and sell quickly, this one-year line can become binding—especially when a casualty event or insurance non-renewal changes the timeline.

A sequencing note: if you’re close to the one-year mark, the question isn’t just “Can we wait a few weeks?” It’s whether waiting changes the full stack (ordinary bracket, NIIT, passive loss release timing, and even buyer terms). Sometimes waiting is worth it; sometimes it’s not, particularly if operational risk or deal risk is rising.

Property character matters: investment vs dealer vs business use

Most Florida rentals are §1231-type business/investment property, not inventory. But if your facts drift into “dealer” activity (property held primarily for sale to customers in the ordinary course), you can lose capital gain treatment and shift profit toward ordinary income treatment. This risk is higher when you have repeated short holds, heavy renovation intent at acquisition, marketing activity that looks like a sales business, or an operating company that behaves like a development pipeline.

The planning move here is not a label. It’s documenting intent, aligning operations with the intended tax posture, and keeping acquisition/renovation/sale cadence consistent with investment character when capital gain treatment is economically important.

Reporting mechanics

Most rental real estate dispositions are reported through Form 4797 and flow into the broader capital gain framework (often with separate handling for §1231 gains/losses, recapture rules, and unrecaptured §1250 gain computations). Reporting mechanics matter because misclassification can distort the NIIT base, loss release, and the character of gain. It’s also where basis errors show up: improvements not capitalized, partial dispositions ignored, and depreciation schedules that do not match reality.

A practical requirement we treat as non-negotiable for sophisticated exits is a basis and depreciation “close file” before listing: original closing statement, capital improvement ledger, depreciation schedules (including cost seg detail), and any casualty/restoration adjustments. The best exit strategies don’t survive weak records.

2026 federal long-term capital gain brackets: the structure high earners must plan around

For sophisticated planning, brackets matter because long-term capital gain rates are determined by taxable income, not by the gain alone. That’s why income stacking and sequencing across years is central.

Below are the 2026 long-term capital gain “maximum rate” thresholds (the top of the 0% band and the top of the 15% band), as published in IRS inflation-adjustment guidance.

| Filing Status | 0% Bracket Up To | 15% Bracket Up To | 20% Applies Above |

|---|---|---|---|

| Married Filing Jointly / Surviving Spouse | $98,900 | $613,700 | Over $613,700 |

| Married Filing Separately | $49,450 | $306,850 | Over $306,850 |

| Head of Household | $66,200 | $579,600 | Over $579,600 |

| Single (All Other Individuals) | $49,450 | $545,500 | Over $545,500 |

Most high-income Florida landlords are already operating in the 15% or 20% long-term band before an exit. In those cases, the bracket table is still useful, but primarily as a capacity map: it tells you whether there is any meaningful headroom to recognize gain in lower brackets, or whether the real value must come from managing NIIT exposure, depreciation-related gain character, and multi-year recognition timing.

A competitor pattern we see in typical online guidance is to stop at “0/15/20.” For sophisticated investors, the practical use is more specific: Which years have capacity, and which years are already saturated by ordinary income and K-1 allocations?

Income stacking and sequencing across tax years: how exits actually get expensive

High earners rarely have a “blank” year. Real estate sales drop into an income stack that already includes operating income, pass-through allocations, portfolio income, and often one-time events. That’s why we treat sequencing as the main planning discipline.

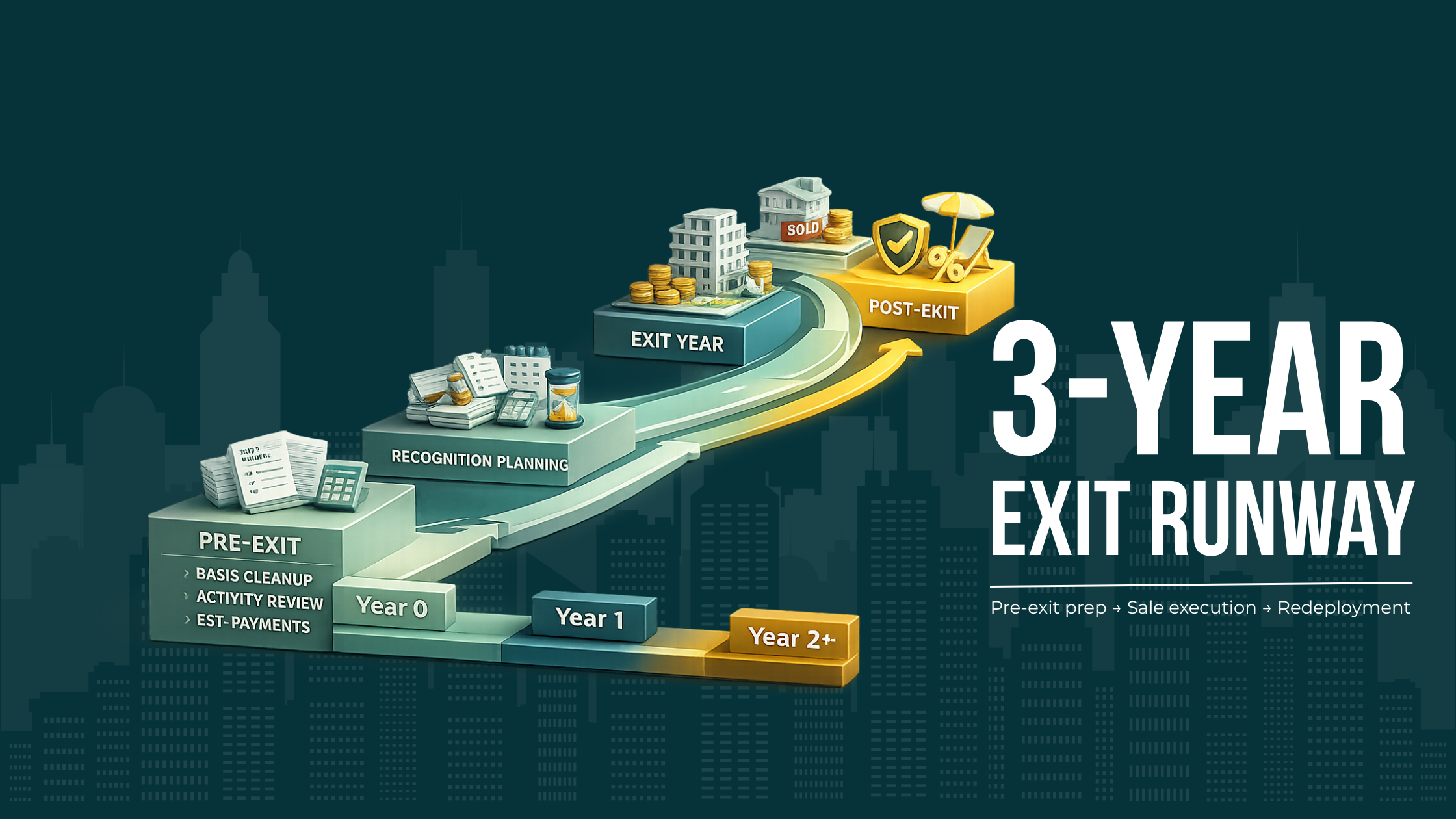

The sequencing principle

Think in windows, not years:

Pre-exit year (Year 0): clean basis, validate activity classification and grouping, map suspended losses, decide whether to accelerate or slow down depreciation, and plan liquidity for taxes and reserves.

Exit year (Year 1): control recognition (timing and structure), manage estimated taxes, and avoid stacking the sale onto peak ordinary income if you have flexibility.

Post-exit year (Year 2+): reinvestment structure, RMD/retirement coordination, and ongoing NIIT posture (especially if you shift from rentals to portfolio income).

Here’s where sequencing becomes real: if your exit year also includes a big bonus, a business sale, unusually high K-1 income, or a large Roth conversion, you may not just pay more tax—you may waste planning tools that only work when you have bracket room (like intentional gain harvesting, loss harvesting, or charitable timing).

Second-order failure mode: many investors only plan for “sale proceeds,” not for the cash timing of taxes. If you plan to reinvest 100% of proceeds and then discover an eight-figure estimated tax obligation mid-year, you can end up selling other assets at the wrong time or taking debt on unfavorable terms. Sequencing should include a tax-liquidity plan that matches the quarter in which gain is recognized.

Multi-property sequencing: Florida landlords commonly have multiple properties with different depreciation profiles. The sophisticated move is not “sell the worst one first.” It’s to consider whether you should sequence dispositions to:

release passive losses in a year when they offset the most expensive income,

avoid bunching multiple unrecaptured §1250-heavy assets into the same calendar year,

and create optionality for exchanges, installment structures, or charitable contributions.

NIIT exposure: the extra 3.8% that Florida landlords can’t ignore

NIIT applies at 3.8% on the lesser of (a) net investment income or (b) MAGI above the statutory threshold. The thresholds for individuals are fixed at $250,000 (married filing jointly), $125,000 (married filing separately), and $200,000 (single/head of household). For high-income landlords, NIIT often applies by default unless you’ve intentionally structured your real estate activity to fall outside the NIIT base.

Why NIIT is a real estate planning issue (not just a portfolio issue)

NIIT generally includes net gains from the disposition of property, including real estate, unless the property is held in a trade or business and the gain is not derived from a passive activity (and not from trading in financial instruments/commodities). In practice, passive vs nonpassive status and how activities are grouped often drive the outcome, but it depends on facts and execution.

New planning layer many competitors omit: NIIT is not only about the sale gain. It’s about what else you did that year that affects MAGI and net investment income:

capital gain distributions,

K-1 income character,

portfolio interest/dividends,

and, for some investors, trust distributions that shift NIIT exposure between the trust and beneficiaries.

NIIT classification and real estate professional strategy (when it applies): If you (or a spouse) qualifies as a real estate professional and materially participates, rental activities may be treated as nonpassive, depending on how the activities are grouped and supported. For some taxpayers, that can reduce NIIT exposure on rental income and potentially on sale gain—depending on facts, grouping elections, and the relationship of the gain to the trade or business. This is not a one-year “status”; it’s an operating posture that must be consistent over time and supported by credible participation and grouping decisions.

Failure mode: assuming NIIT is “automatic” and therefore not worth planning around. For high earners in Florida, NIIT can be the difference between an exit that is merely expensive and an exit that is expensive plus inflexible. If the sale is unavoidable, the planning question becomes: can we reduce net investment income in that year (without harming the portfolio), or should we recognize the gain in a year where other investment income is lower and the NIIT base is narrower?

Another failure mode: assuming that holding real estate inside an entity automatically changes NIIT. Entity form changes how income is reported and allocated; it does not automatically remove NIIT. Classification and the character of the activity still matter.

Exit planning mechanics: depreciation recapture and unrecaptured §1250 gain in plain English

When you depreciate a rental, you reduce basis. When you sell, the IRS requires you to separate gain into buckets, because not all gain is taxed the same way.

Unrecaptured §1250 gain (the “real estate depreciation bucket”)

For depreciated real property, the portion of gain attributable to depreciation (generally the depreciation you were allowed or allowed to take) is treated as unrecaptured §1250 gain and taxed at a maximum 25% rate under the federal framework. Importantly, that 25% is a cap on this category of gain, not a statement that the gain is “ordinary income.”

The planning implication is structural: long-held Florida rentals often have a large unrecaptured §1250 component. If you’ve owned the property for years, the depreciation bucket can represent a meaningful share of total gain—especially when the property appreciated and you consistently depreciated improvements.

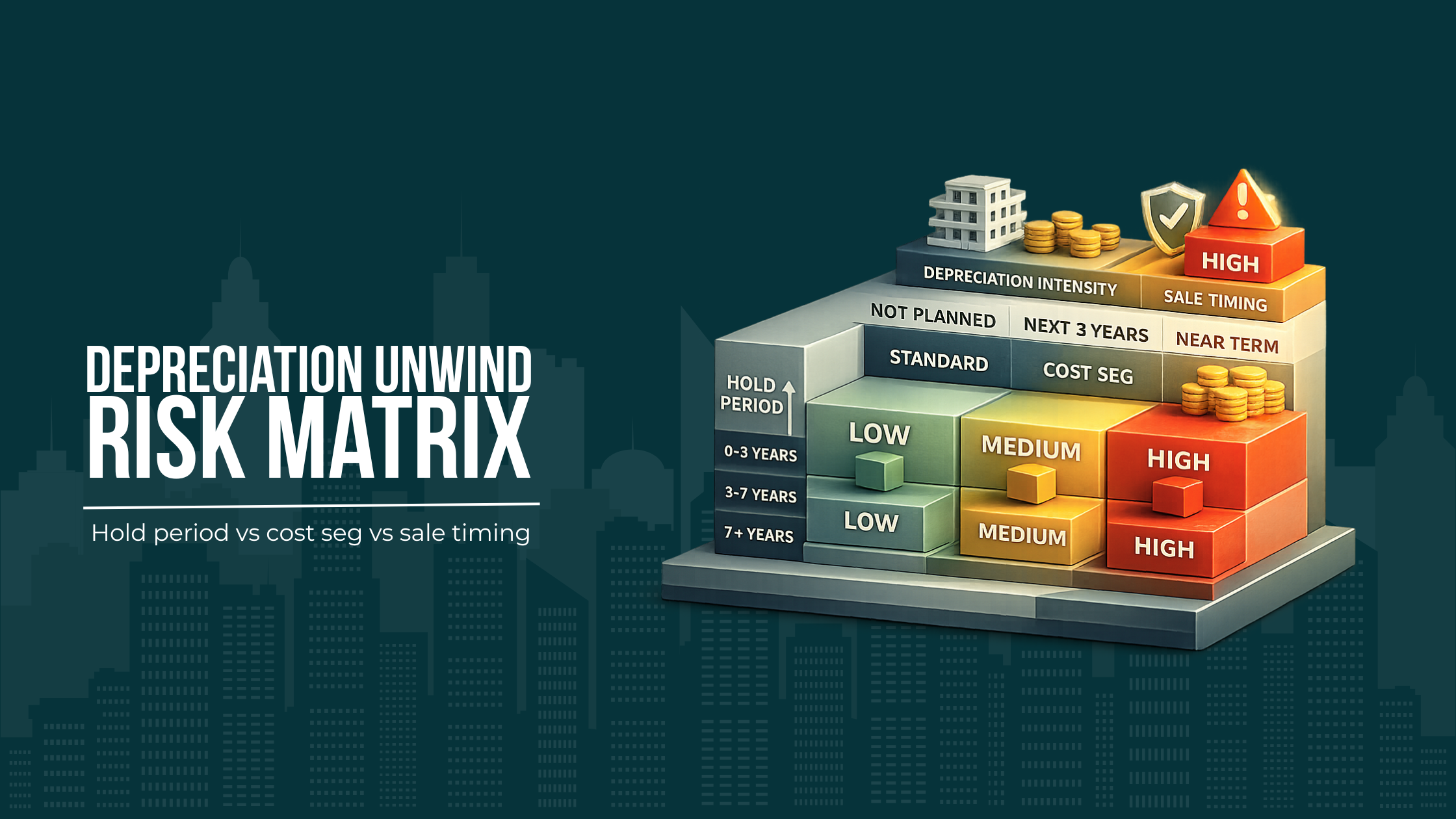

Recapture can be larger than investors expect after cost segregation

Cost segregation frequently reclassifies components of the building into shorter-lived property (often §1245 property like certain personal property components and land improvements). Those components can be subject to ordinary income recapture on disposition to the extent of depreciation taken on those components. That is one reason cost segregation improves cash flow early but can produce a more complex (and potentially more expensive) unwind if you sell sooner than planned.

Unwind scenario we plan for: a property is cost-segregated, you take large accelerated depreciation, and then a non-tax event forces an earlier sale (insurance non-renewal, special assessment, litigation risk, tenant concentration risk, or a partner divorce). If the sale occurs before the time value of money has “paid you back” for the accelerated depreciation, the exit can feel like giving back the benefit at the worst moment.

Another second-order effect: depreciation recapture is based on depreciation allowed or allowable. If your records are incomplete or depreciation was incorrectly taken (or not taken), the sale-year cleanup can be expensive and time-consuming. For sophisticated investors, clean depreciation schedules are not bookkeeping—they’re exit infrastructure.

Cost segregation (and bonus depreciation when applicable): use it as a planning tool, not a reflex

Cost segregation is often positioned as a near-automatic move: “accelerate depreciation, improve cash flow.” For high-income Florida landlords, the better question is: What is our intended hold period and exit path, and what does cost seg do to the after-tax exit?

When cost seg tends to help

You have sustained high ordinary income and can use the deductions without building trapped passive losses.

You expect a long hold period, so the time value of money dominates the unwind.

You have a credible reinvestment strategy (including a possible exchange path) and the operational plan supports that hold.

A sophisticated use-case is using cost segregation as part of a capital redeployment plan: you’re intentionally pulling cash forward to fund improvements or acquisitions that raise after-tax wealth over a multi-year horizon, not simply lowering this year’s tax bill.

When cost seg can backfire

You are likely to sell earlier than planned (or are in a market where forced timing events are plausible).

You have limited passive-loss usability and are effectively creating suspended losses that do not improve after-tax liquidity.

You are already in a position where NIIT and unrecaptured §1250 exposure will be binding, and accelerating depreciation increases the size of the depreciation-related gain buckets without improving your reinvestment flexibility.

Bonus depreciation (decision logic): bonus depreciation rules have changed over time and depend on placed-in-service dates and property type. Rather than chasing a percentage, we use a decision rule: accelerate only when (1) you can use the deductions, (2) the hold plan is credible, and (3) the exit plan has an unwind path that you would accept even if the market forces your timing.

Unwind control lever: if a sale is likely within a defined horizon, cost segregation may still be useful, but it should be paired with an explicit unwind strategy (exchange feasibility, installment options, charitable capacity, and liquidity reserves for taxes).

Entity and ownership structure implications: how gains flow and where flexibility lives

Entity structure determines who recognizes gain, how losses are used, how allocations work, and where NIIT exposure lands. It also determines what you can do when a buyer appears and wants a fast close.

Common Florida landlord structures and why they matter at exit

Disregarded entities (single-member LLCs):

Clean reporting and direct control. But there’s limited ability to shift allocations or tailor outcomes across owners because there aren’t multiple owners. NIIT outcomes depend largely on passive vs nonpassive classification at the owner level and the owner’s MAGI stack.

Partnerships / multi-member LLCs:

Partnerships create planning flexibility through allocations and deal terms, but they also create exit friction when partners have different objectives (exchange vs cash-out, different tax brackets, different liquidity needs). A partnership sale can trigger gain at the partner level, and the character/NIIT exposure can vary by partner facts and how the activity is treated.

S corporations (often structurally awkward for appreciating real estate):

S corps can create rigidity around basis, distributions, and built-in appreciation strategies. Many investors with S-corp-held real estate discover at exit that the structure limits optionality and can complicate partial exits or partner-specific planning.

Trust ownership:

Trusts reach higher marginal rates quickly, and NIIT can apply at relatively low income levels for trusts compared to individuals. That means estate planning choices can materially change after-tax exit outcomes, especially for portfolios where real estate produces both ongoing income and sale gains.

New paragraph competitors usually miss: exit flexibility is often created years in advance. If you have multiple owners and you want optionality (one partner exchanges, another exits), the feasibility often depends on how long the structure has been in place, how clean capital accounts and debt allocations are, and whether your operating agreement supports the intended flexibility. When investors wait until the buyer’s LOI arrives, the only remaining options are the ones that can be implemented under time pressure—which are usually the least elegant.

Deal-structure spillover: entity form can also influence what buyers will accept. Some buyers prefer asset deals; others prefer entity purchases. The tax and legal trade-offs in those deal forms can push gain character and timing in different directions. The earlier you model this, the less likely you are to accept a buyer-friendly structure that is tax-inefficient for you.

Active vs passive treatment: why it becomes binding at the sale

Most investors understand that passive losses can be suspended. The sophisticated problem is the interaction between passive status, NIIT, and what happens in the year of disposition.

Suspended passive losses: valuable, but only in the right year

Suspended passive losses can be released when you dispose of your entire interest in a passive activity in a fully taxable transaction. In the right year, that release can materially change the after-tax cost of a sale. In the wrong year, it can be underutilized or offset income that would have been taxed more favorably anyway.

Planning move: we treat suspended losses as a timing asset. We ask: in which year would releasing these losses create the highest after-tax value? That answer depends on what other income you expect (operating income, other gains, RMDs) and whether you anticipate using an exchange or installment structure that changes recognition timing.

Real estate professional status and grouping: exit-year consequences

Real estate professional status and material participation can shift rentals from passive to nonpassive for some taxpayers. Grouping elections can also matter because they determine how activities are measured for participation and how income/losses are aggregated.

Second-order effect: grouping decisions are often made for annual loss usability, but they can have exit-year consequences. If you group activities and later sell one property, you need to understand whether you sold an entire activity or a component of a larger grouped activity, and what that does to loss release and NIIT classification. The exit-year surprises in this category are almost always due to planning that focused on annual deduction capture rather than the disposition mechanics.

Cash flow vs long-term tax efficiency: where “good strategies” backfire

For Florida landlords, cash flow is not optional. But cash flow decisions can create long-term tax friction if they ignore the unwind.

Common trade-offs we model explicitly:

Accelerated depreciation vs exit concentration: accelerating depreciation can improve interim cash flow, but it can increase depreciation-related gain and, for cost-segregated components, ordinary recapture exposure.

Refinance proceeds vs future flexibility: tax-free refinance proceeds can fund growth, but debt structure can constrain later sale structures and reduce flexibility in partner allocations.

Loss creation vs loss usability: creating losses that cannot be used (because of passive limitations, basis limits, or at-risk constraints) can produce a “paper win” that does not improve after-tax liquidity.

Timing wins vs operational risk: waiting for a better tax year can be rational, but only if the operational risk (insurance, tenants, capex) doesn’t increase faster than the tax benefit.

New paragraph: cash flow planning should include a tax reserve policy. Florida investors often reinvest aggressively and treat taxes as a future problem. A defined tax reserve policy (especially in sale years) is not conservative for its own sake; it prevents forced asset sales or expensive borrowing when estimated taxes come due.

Retirement / pension / RMD coordination: the hidden accelerator of exit-year tax

High-income investors often underestimate how retirement income interacts with a real estate sale.

RMDs and pension income create a baseline of ordinary income that you cannot “turn off,” reducing your ability to place gain into lower brackets.

A large sale can raise MAGI, which increases exposure to NIIT and other MAGI-linked outcomes.

If you’re doing Roth conversions, a sale year can turn an otherwise efficient conversion plan into an expensive stacking event.

New planning approach: we often map a 3–7 year horizon that includes (1) pre-RMD years, (2) conversion years (if any), and (3) likely disposition windows. Then we decide whether the sale should occur before RMDs begin, after major conversions are completed, or in a year where other income sources are intentionally lighter.

Second-order failure mode: investors sometimes time a sale “after retirement” assuming income will be lower, but then discover that K-1 income remains high, RMDs start, and portfolio income replaces earned income. The correct question is not “Am I working?” It’s “What is my taxable income stack in that year?”

Asset-based planning vs “deduction-first” planning: what sophisticated landlords do differently

Deduction-first planning asks: What can we deduct this year?

Asset-based planning asks: What is the after-tax path of each asset, and how do the assets interact across years?

For Florida real estate investors, asset-based planning typically includes:

A property-by-property basis and depreciation map (including cost seg detail and improvement history)

A sale scenario model (sell now, sell later, exchange, partial disposition, installment, charitable planning where appropriate)

A NIIT classification plan (passive/nonpassive posture, grouping strategy, and how it interacts with your broader investment income)

An entity and ownership review focused on exit flexibility (allocations, partner objectives, trust involvement, and liquidity constraints)

A risk plan for casualty events and forced sales (insurance non-renewal, major capex, tenant disruption)

New paragraph: treat planning capacity as scarce. Most high earners have limited bandwidth for annual tax tactics. Asset-based planning reduces the number of decisions by setting a coherent policy: which assets are “hold-and-defend,” which are “exchange candidates,” which are “dispose-and-redeploy,” and what triggers a change in classification (insurance costs, capex threshold, partner events).

Scenario-based examples: sequencing logic over three years

These are not simplistic “$X write-off” examples. They show how sequencing changes outcomes.

Example 1: The “collision year” vs the “runway year”

Facts: A Florida physician with $600k+ of ordinary income plans to sell a long-held rental with significant depreciation.

Collision year: sells in the same year as peak compensation and a large K-1 allocation. Result: the gain stacks on top of high ordinary income, NIIT is fully engaged, and the depreciation-related gain bucket is recognized in the same year.

Runway plan: uses a pre-exit year to reduce ordinary-income spikes where feasible (compensation timing, discretionary business spending decisions, distribution planning), validates passive loss position, and structures sale timing so the gain year is lighter on other income.

New angle: the runway year can also be used to create optionality—evaluating exchange feasibility, documenting participation status, and deciding whether charitable contributions (if part of your plan) should be funded in the exit year or earlier.

Example 2: Cost segregation without an exit plan

Facts: Investor cost-segregates a Florida short-term rental, generating large early depreciation. Two years later, insurance costs and operating volatility push an earlier sale than expected.

Accelerated depreciation improved interim cash flow.

Early sale concentrates depreciation-related gain into a short window and may create ordinary recapture exposure for §1245 components.

Suspended passive losses (if any) may or may not be usable depending on activity classification and disposition structure.

New angle: if the sale is forced, the question becomes whether you can change recognition timing (installment structure), change reinvestment path (exchange), or at least ensure that passive loss release aligns with the recognition year. Forced sales are not rare in Florida; planning should assume they are possible.

Example 3: Partnership misalignment at sale

Facts: Two partners own an appreciating Florida rental. Partner A wants to exchange; Partner B wants to cash out.

Without advance planning, the entity often must choose one path, creating a value transfer from one partner to the other (in the form of foregone deferral or foregone liquidity). With advance planning—clean books, clear capital accounts, and governance that supports flexibility—there may be ways to improve outcomes, but those options usually require time.

New angle: misalignment isn’t only “exchange vs cash.” It’s also about timing: one partner may need a sale this year for liquidity; the other may prefer to sell next year to avoid stacking onto other income. Multi-owner planning must include a calendar, not just a strategy label.

1031 exchange Florida rental property: strategic use and common constraints

A properly structured like-kind exchange can defer recognition of gain by rolling into replacement property. For sophisticated Florida landlords, the decision is not “Should we do a 1031?” It’s whether deferral aligns with your capital allocation and risk posture.

Key decision factors:

Asset allocation: are you deferring tax to stay in Florida real estate, or are you trying to reduce Florida-specific risk (insurance/casualty) by redeploying to different markets or property types?

Quality constraints: can you find replacement property you would buy even without the tax deferral?

Timeline and execution risk: exchanges are operationally rigid. If you can’t execute, the planning value collapses.

New paragraph: exchanges and cost segregation interact. If you’ve accelerated depreciation aggressively, deferral through an exchange can preserve the time value of that acceleration, but it can also carry forward complex depreciation profiles into the replacement property. That isn’t bad; it just means you should treat depreciation planning as portfolio-level, not property-level, once you begin exchanging.

Installment sale planning: controlling recognition when full liquidity isn’t required

An installment sale can spread gain recognition over time, which can reduce bracket compression and help manage NIIT and ordinary-income stacking across years.

For high-net-worth Florida landlords, installment planning is often less about “saving tax” and more about aligning:

liquidity needs,

reinvestment timing,

and the tax year(s) in which income is recognized.

New paragraph: installment trade-offs are real. You exchange tax timing for buyer credit risk, potential pricing concessions, and legal complexity. If you are selling in a period of elevated insurance uncertainty or tenant volatility, credit risk can be the dominant variable. Installment planning works best when you would accept the buyer risk even without the tax benefit.

Correcting common misuse and oversights

This is where high earners lose real money—not because the rules are hidden, but because planning is fragmented.

1) Treating “capital gains rate” as the whole answer

Real estate sales are multi-bucket. Ignoring depreciation-related gain and NIIT leads to under-withholding, surprise estimates, and poor reinvestment decisions. Unrecaptured §1250 gain has its own maximum-rate treatment, and cost segregation can introduce ordinary recapture components.

2) Doing cost segregation without modeling the unwind

Cost seg can be excellent—but without a hold/exit plan, it can convert a future sale into a concentrated recognition event with less flexibility than investors expect.

3) Assuming passive losses will offset everything at sale

Suspended losses can be powerful, but only if the disposition is structured correctly and the activity tracking is clean. Investors often discover in the exit year that losses are trapped, misgrouped, limited by basis/at-risk rules, or released in a year where they offset lower-value income.

4) Ignoring NIIT classification until the closing table

NIIT thresholds are low relative to high-income investors, and NIIT can reach rental income and real estate gains unless an exception applies based on trade or business and passive activity characterization. The time to build the posture is during the hold period, not after the buyer signs.

5) “Entity inertia”

Investors keep legacy structures long after they stop serving the strategy. The cost shows up at exit: allocation constraints, partner misalignment, trust-level compression, and avoidable tax concentration.

6) Underestimating Florida’s forced-timing risk

Insurance market volatility, storm-driven repairs, and casualty events can force earlier sales or accelerate capex. If your plan assumes perfect timing, it will fail precisely when you need it most.

New paragraph: not every deferral is a win. Exchange or deferral strategies can create a “tax tail wagging the investment dog” dynamic, where you accept a weaker deal, weaker market, or misaligned asset just to avoid recognizing gain. For sophisticated investors, the correct metric is after-tax, after-risk return—not tax deferral at any price.

We’ll review entity and ownership structure for allocation flexibility and exit-year bracket stacking, especially in multi-owner deals.

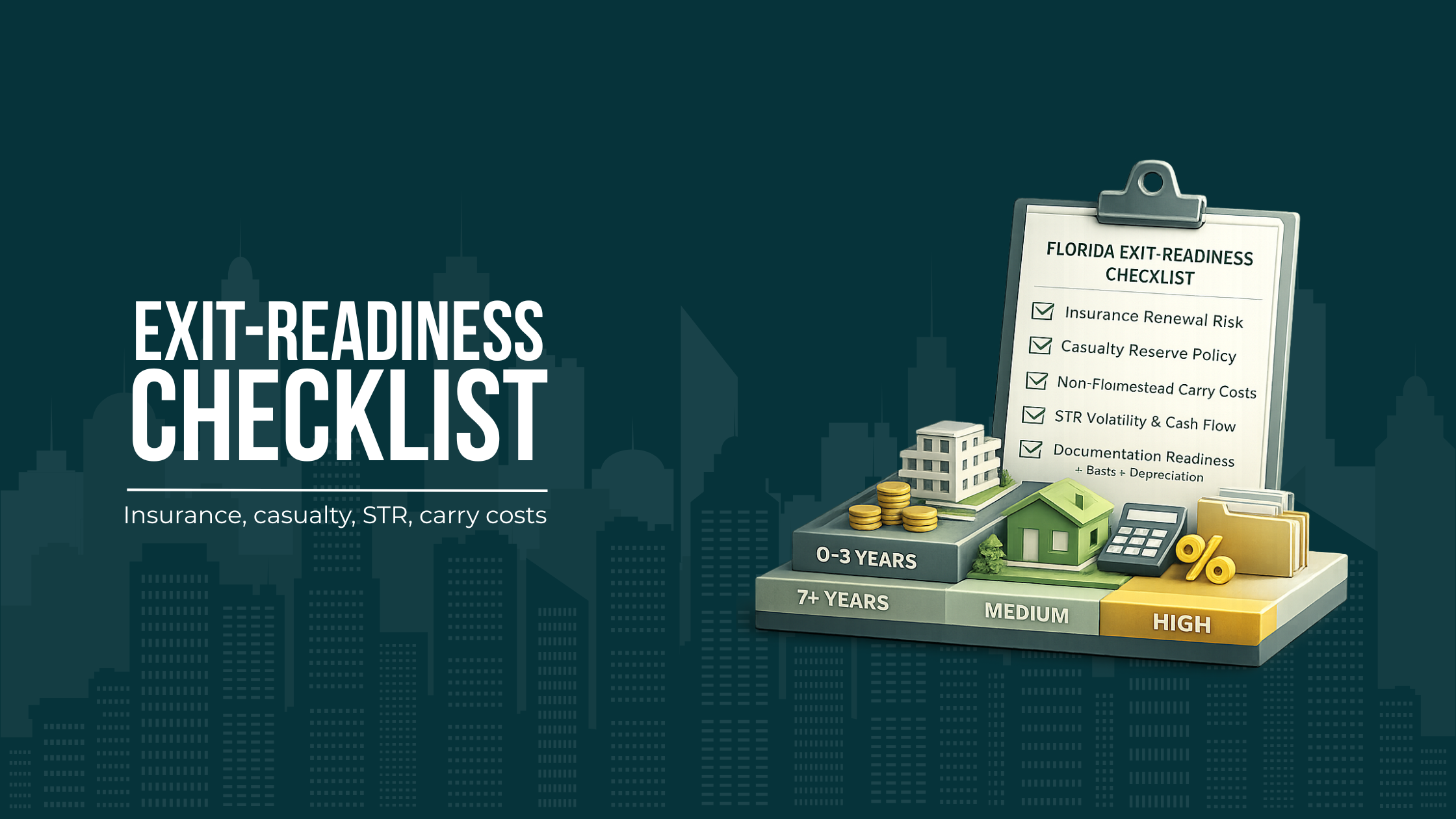

Florida-specific planning considerations

Florida changes the analysis in ways sophisticated investors should model explicitly. Florida changes exit planning because timing is often driven by operating risk, not just tax preference.

If more than a few boxes are unresolved, we treat the portfolio as ‘timing constrained’ and design sequencing with less reliance on perfect calendars.

1) No state income tax increases the importance of federal optimization

In high-tax states, planning often focuses on state sourcing and state brackets. In Florida, those variables are largely absent for individuals, which means federal planning levers carry more weight: long-term capital gain brackets, NIIT posture, depreciation-related gain, and recognition timing.

New paragraph: Florida also changes your “move timing” incentives. Investors relocating into Florida sometimes assume the move itself solves the problem. It doesn’t. Florida residency removes state income tax exposure, but the federal exit stack (including NIIT and unrecaptured §1250 gain) remains. The win comes from coordinating the timing of exits with the broader federal picture, not from the zip code alone.

2) Florida real estate concentration amplifies recapture risk

Florida investors often hold multiple depreciated properties for long periods. That creates a portfolio-level “recapture footprint.” Even if each property is manageable, the combined depreciation profile can produce a large unrecaptured §1250 and recapture exposure when you begin exiting.

New paragraph: concentration also changes your risk-adjusted sequencing. If your portfolio is heavily Florida coastal exposure, a rational strategy might be to exit or reduce exposure earlier than your tax model prefers. In that case, sequencing is about damage control: choosing which assets to sell first, which can be exchanged, and how to avoid bunching multiple depreciation-heavy dispositions into one year.

3) Property tax structure implications (homestead vs non-homestead) as they affect hold/sell decisions

Florida’s property tax structure creates meaningful differences between homesteaded primary residences and non-homesteaded investment property. Without turning this into a local law explainer, the planning implication is simple: your carry cost trajectory affects your hold economics, which affects whether deferral strategies make sense.

New paragraph: carry costs can change your “best tax strategy.” When non-homestead property taxes and insurance escalate faster than rents, investors sometimes keep a property solely because selling creates a tax bill. That is a form of value destruction. A disciplined approach compares (1) after-tax proceeds and redeployment return versus (2) after-tax hold return under realistic carry-cost assumptions.

4) Insurance/casualty/climate risk implications for timing, reserves, and exit planning

Florida landlords face a higher probability of sudden insurance premium increases, non-renewals, major deductibles, and casualty events that disrupt tenants and operating income. These are not just operational risks; they are tax-planning risks because they can force timing.

New paragraph: treat forced timing as a base-case scenario, not a tail event. If a casualty event triggers major repairs, you may face a choice between injecting capital, accepting vacancy risk, or selling earlier than planned. Each option interacts with depreciation, basis, and exit-year income stacking. That is why we build a liquidity reserve policy and keep exit documentation ready: basis records, depreciation schedules, and entity governance should be “sale-ready” even when you intend to hold.

We’ll evaluate passive vs nonpassive posture and how it may change NIIT layering across the sale year and surrounding years.

Conclusion: treat the sale as a capital event, not a tax form

For Florida landlords, capital gains real estate tax Florida outcomes are determined long before the property is listed: your hold timeline, depreciation strategy, passive vs nonpassive posture, entity structure, and how you sequence income across years.

The objective is not to minimize tax in isolation. It’s to coordinate a multi-year strategy that controls income stacking, manages NIIT exposure, anticipates depreciation-related gain, and aligns exit mechanics with reinvestment and retirement timing.

When the advisory team is fragmented, the exit becomes reactive and the federal stack punishes reaction. A coordinated plan turns the sale into a designed outcome: fewer surprises, more flexibility, and a cleaner redeployment of capital into the next stage of your portfolio.

We’ll build a multi-year sequencing plan that coordinates gain recognition with recapture exposure and your operating-income peaks.

Frequently asked questions

How do we decide whether to sell in a high-income year or intentionally wait for a “lighter” year?

For high-income Florida landlords, the decision is rarely about the long-term capital gain bracket alone. We weigh (1) what else will be in your income stack in each candidate year (business profit volatility, K-1 character, portfolio income, retirement income baselines), (2) whether waiting creates meaningful bracket or NIIT leverage, and (3) the operational risk of waiting (insurance renewals, tenant concentration, capex timing, and casualty exposure). A “lighter” year is only valuable if it’s credible and not purchased with higher investment risk or weaker deal terms.

How should we sequence multiple property sales without creating an “exit-year pileup”?

We typically sequence to avoid bunching the most depreciation-heavy assets into the same recognition year and to preserve optionality. That can mean spreading dispositions across calendar years, pairing a sale with a year where other investment income is lower, and intentionally timing the release of any suspended passive losses to offset the most expensive income. We also consider operational drivers: properties with rising insurance/casualty risk or deteriorating carry economics may need to exit earlier even if the tax model prefers waiting. Sequencing should be portfolio-level, not property-by-property in isolation.

What’s the most common “unwind surprise” with depreciation when selling long-held Florida rentals?

The surprise is not that depreciation reduces basis. It’s how large the depreciation-related gain bucket becomes and how it changes the character of income at sale. Long holds plus consistent depreciation can create a meaningful unrecaptured §1250 component even when the headline story is “appreciation.” If cost segregation was used, certain components can create ordinary-recapture exposure as well. The practical implication is that you don’t want to discover your true depreciation footprint at closing. We treat depreciation schedules and component detail as exit infrastructure that must be validated before marketing the asset.

If we used cost segregation, what long-term consequences should we model before committing to a sale path?

Cost segregation is a timing shift with a payback profile. Before choosing an exit path, we model how much of the accelerated depreciation is likely to reappear as depreciation-related gain and whether any portion may be taxed less favorably due to component recapture. Then we test the exit options against your holding horizon and reinvestment plan: a long hold can allow time value of money to dominate, while an earlier sale can concentrate the unwind. We also evaluate whether the exit needs flexibility (installment timing or exchange feasibility) to avoid stacking the unwind into a peak-income year.

How do we think about “partial exits” or staged liquidity without unintentionally worsening tax character?

Sophisticated exits often involve staged liquidity: selling a portion, recapitalizing, or exiting one property while holding others. The risk is unintentionally creating recognition events that don’t align with your planned sequencing, especially when depreciation profiles differ across assets or owners. We focus on what is actually being disposed of (and how that affects gain character and loss release), how proceeds will be redeployed, and whether the staged approach creates a new “stacking problem” in later years. The best staged plan includes a calendar for recognition, not just a target allocation.

In multi-owner deals, what entity/ownership issues tend to reduce flexibility at disposition?

The constraint is usually not the entity label. It’s the combination of partner objectives, allocation mechanics, debt structure, and governance. Partnerships can offer flexibility, but only if capital accounts, allocations, and operating agreement terms support the intended outcome when one partner wants liquidity and another wants deferral. Trust ownership can compress outcomes if the trust retains income or if distributions are misaligned with the tax posture. We plan for exit flexibility early by clarifying partner pathways, documenting economic intent, and keeping reporting and capital tracking clean so the deal doesn’t force a one-size-fits-all outcome.

How does Florida’s environment change “hold vs sell” decisions beyond the lack of state income tax?

Florida’s no state income tax increases the weight of federal planning, but Florida-specific operating realities often drive timing. Insurance volatility, casualty exposure, and climate-driven repair risk can force earlier-than-planned decisions or change the required reserve policy. For non-homestead properties, carry costs can rise in ways that alter the hold economics even if the tax model favors deferral. Short-term rental activity adds operational variability that can affect holding-period confidence and exit readiness. We incorporate these factors as first-order inputs, not footnotes, because forced timing is a real constraint in Florida portfolios.

When does “waiting for better tax timing” become a mistake for Florida landlords?

Waiting becomes a mistake when the tax benefit is smaller than the investment risk or opportunity cost you’re absorbing. If insurance renewal risk, rising carry costs, tenant volatility, or capital expenditure needs are increasing faster than the expected tax advantage of delaying, the strategy can destroy after-tax wealth even if it reduces a rate on paper. Another failure mode is waiting without building exit readiness: if a forced sale occurs and your basis, depreciation detail, and ownership documentation aren’t prepared, you lose the ability to execute higher-quality timing or structure choices under pressure.