Short-Term vs Long-Term Rentals: Tax Strategy Differences That Matter Over a Decade

For high-income Florida taxpayers, rental real estate is rarely just about yield. It is a capital allocation decision with tax consequences that compound over time.

Short-term rentals and long-term rentals can both work. But they do not behave the same once you factor in depreciation timing, active versus passive treatment, entity structure, exit planning, and how those choices interact with a broader, multi-year tax strategy.

Most articles flatten this decision into surface-level comparisons. Nightly rates versus monthly rent. Flexibility versus stability. Those details matter operationally, but they are not what drives after-tax outcomes over a decade.

This article is written for investors and business owners who already understand the basics and want to make the right structural choice before the first return is filed.

Key Takeaways

The tax value of short-term rentals is driven by timing and classification, not just higher income.

Long-term rentals often win on durability and exit efficiency, not annual deductions.

Cost segregation and accelerated depreciation tools, including bonus depreciation where available.

Entity structure can amplify or neutralize the benefits of either strategy.

Recapture, sale timing, and future liquidity matter more than year-one tax savings.

Florida’s tax environment shifts the analysis toward federal optimization and asset protection, not state arbitrage.

Evaluate short-term and long-term rental decisions within a 10-year tax plan.

The Strategic Difference Between Short-Term and Long-Term Rentals

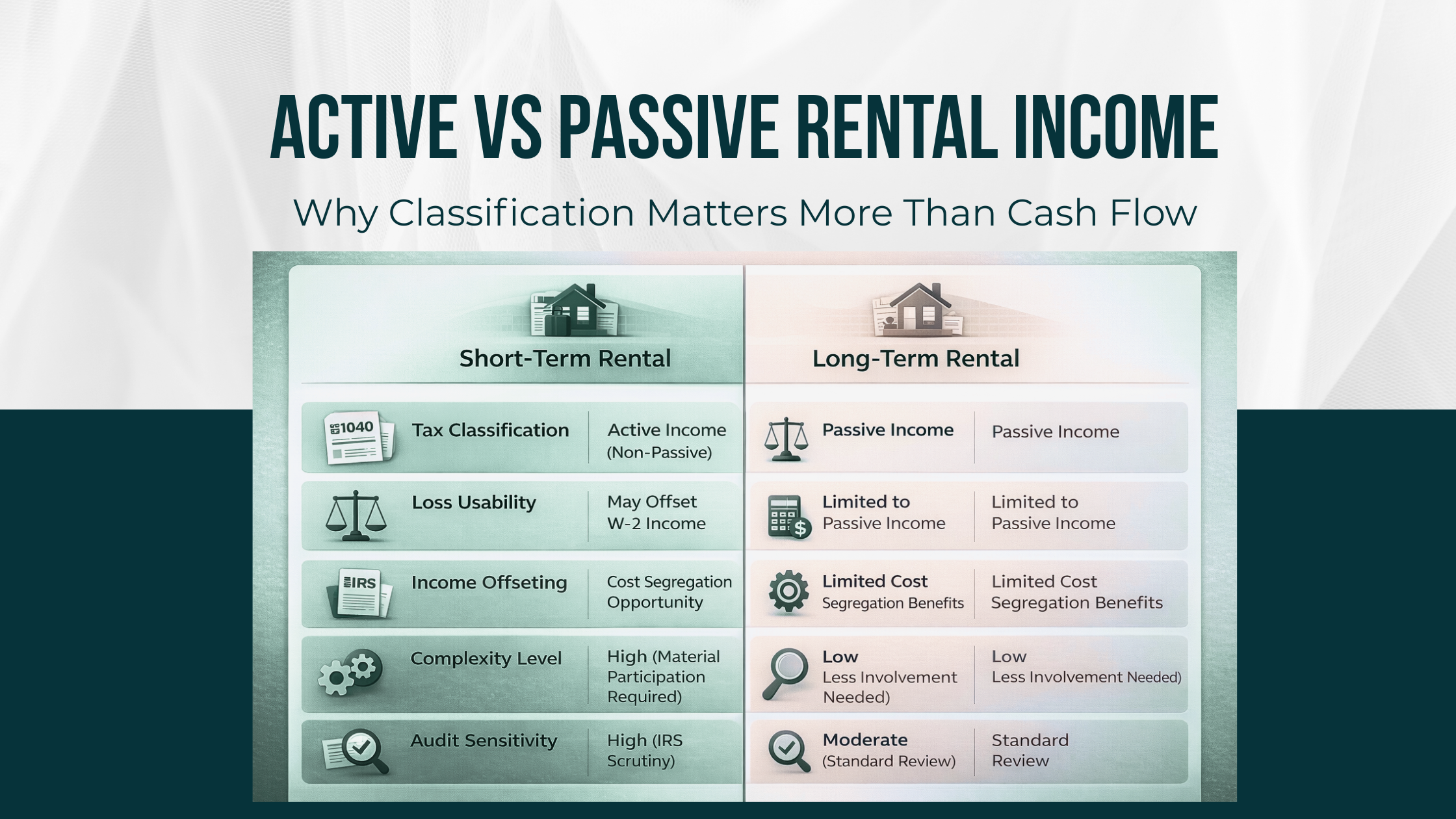

At a high level, the tax distinction is not about property type. It is about how the activity is treated.

Short-term rentals can qualify as active business income under certain conditions. Long-term rentals are generally passive by default.

That difference affects how losses are used, how depreciation interacts with other income, and how the asset fits into a broader tax plan.

Over a ten-year horizon, the classification decision often outweighs the income difference itself.

Short-Term Rentals: Active Treatment and Accelerated Outcomes

When Short-Term Rentals Are Treated as Active

Short-term rentals may be treated as a non-rental trade or business for passive activity purposes when average stay length and participation thresholds are met.

If those participation and classification tests are not met, expected deductions may instead become suspended passive losses rather than usable offsets.

This is why short-term rentals attract high earners seeking near-term tax relief.

But the benefit is front-loaded. The planning question is not whether it works in year one. It is whether the outcome still makes sense in year seven or ten.

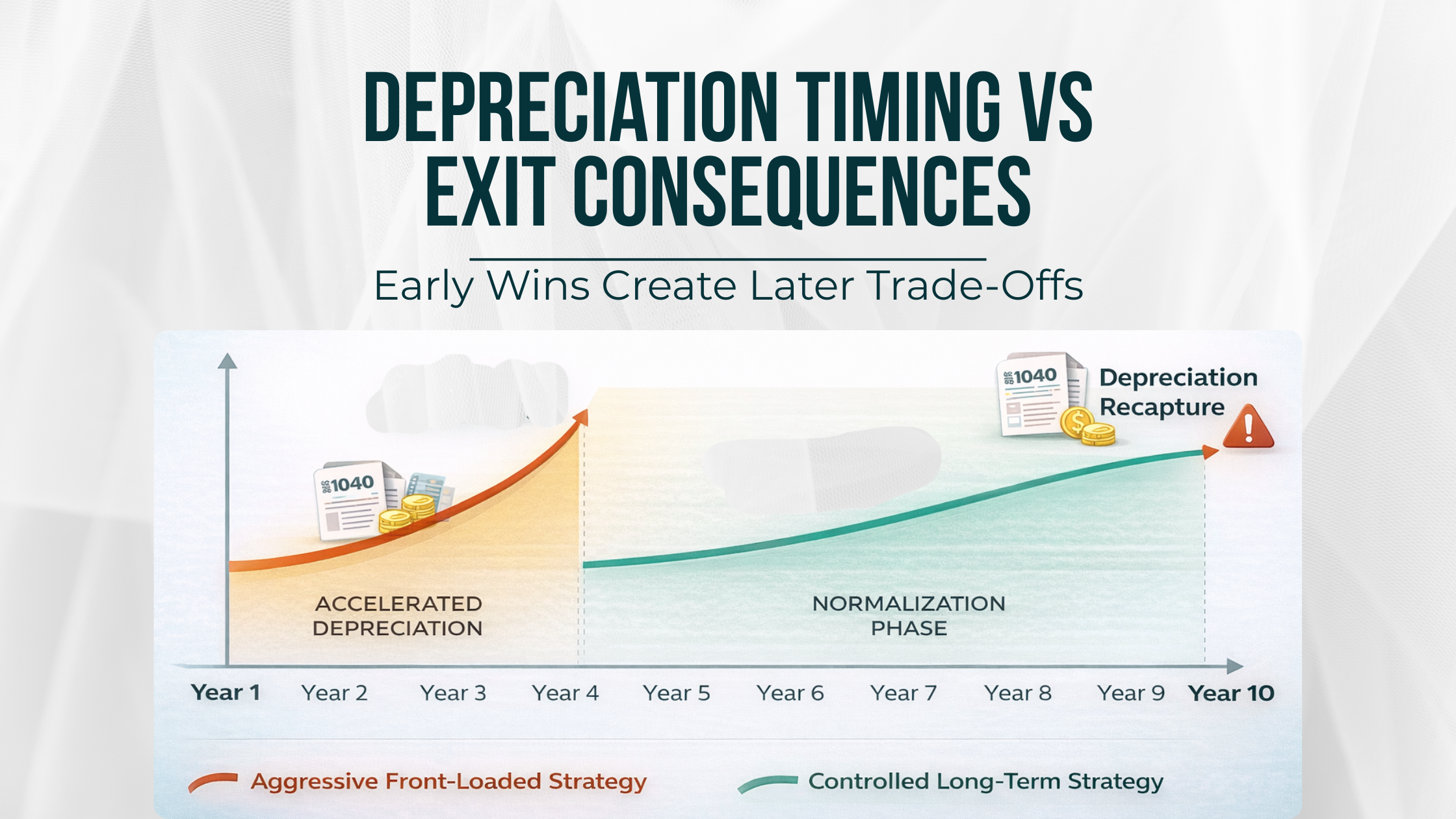

Depreciation Timing and Income Mismatch

Short-term rental strategies often rely on accelerated depreciation to create large early losses.

That can be effective when income is peaking or when liquidity needs are high. But it also increases future exposure to recapture and reduces flexibility at exit.

The key is aligning depreciation timing with income cycles, not chasing deductions in isolation.

Long-Term Rentals: Passive Stability and Compounding Efficiency

Passive by Design, Strategic by Choice:

Long-term rentals are usually passive. For many investors, that is a feature, not a flaw.

Passive classification creates predictability. It simplifies reporting, reduces audit friction, and pairs well with long-term holding strategies.

Losses may be deferred, but the asset often produces cleaner outcomes at sale and greater flexibility for estate and succession planning.

The primary exception is qualification as a real estate professional combined with material participation, which can recharacterize long-term rental activity as non-passive.

Depreciation as a Long-Term Lever:

Depreciation on long-term rentals tends to be slower and steadier.

Over time, this can align better with appreciation, refinancing strategies, and planned exits. When combined with disciplined capital improvements, the tax benefit compounds quietly rather than spiking early.

Cost Segregation: Strategy Tool, Not a Tactic

Cost segregation is often discussed as a universal solution. It is not.

Short-Term Rentals and Front-Loaded Benefits:

In short-term rentals, cost segregation can amplify early losses and increase the ability to offset active income.

That can be powerful, but only if there is a plan for recapture and future income normalization.

Long-Term Rentals and Controlled Acceleration:

For long-term rentals, cost segregation must be used selectively.

Over-accelerating depreciation can distort long-term returns and reduce exit efficiency. In many cases, partial or delayed segregation produces better lifetime results.

Entity and Ownership Structure Implications

Single-Asset LLCs vs Operating Entities:

Short-term rentals often resemble operating businesses. This can justify different entity structures, including management entities or multiple LLC layers.

Long-term rentals are typically simpler. Overcomplication can erode returns without adding meaningful tax benefit.

Self-Employment and Payroll Considerations:

Short-term rental income may be exposed to self-employment tax when substantial guest services are provided, which should be evaluated when designing the operating model and entity structure.

Long-term rentals generally avoid these issues, making them easier to integrate into broader wealth structures.

Align rental classification, entities, and depreciation before problems compound.

Cash Flow Versus Tax Efficiency Over Time

High earners often overweight tax savings and underweight cash flow resilience.

Short-term rentals may produce higher gross income but also higher volatility, expenses, and regulatory risk.

Long-term rentals tend to generate steadier after-tax cash flow and are easier to finance, insure, and hold through cycles.

Over a decade, stability often wins.

Exit, Recapture, and the Cost of Early Wins

Depreciation Recapture Reality:

Accelerated depreciation does not disappear. It reappears at sale.

Short-term rental strategies that maximize early deductions often face heavier recapture and higher effective tax rates later.

Long-term rentals, when held and exited deliberately, often produce smoother outcomes.

The magnitude and character of recapture depend on the mix of §1245 versus §1250 property identified, as well as the chosen exit method.

Liquidity and Optionality:

An asset that is easy to sell, refinance, or transfer has strategic value.

Long-term rentals usually offer more exit paths with fewer tax surprises.

Understand recapture, timing, and exit consequences before committing capital.

What Most Articles Get Wrong or Leave Out

Overemphasis on Year-One Savings:

Many articles focus on immediate deductions without modeling long-term consequences.

High earners do not need more deductions. They need better sequencing.

Ignoring Entity and Exit Planning:

Rental strategy decisions are often made without considering how the asset will be owned, sold, or transferred.

This is where most planning failures occur.

Treating Cost Segregation as Automatic:

Cost segregation without a long-term plan often creates more problems than it solves.

Situations Where Caution Is Required

Short-term rentals may be less effective when:

Income is already volatile

Time participation thresholds cannot be met

Exit timing is uncertain

Financing and insurance costs erode returns

Long-term rentals may underperform when:

Loss utilization is a priority

Capital is needed quickly

Active income sheltering is a core objective

No strategy is universal.

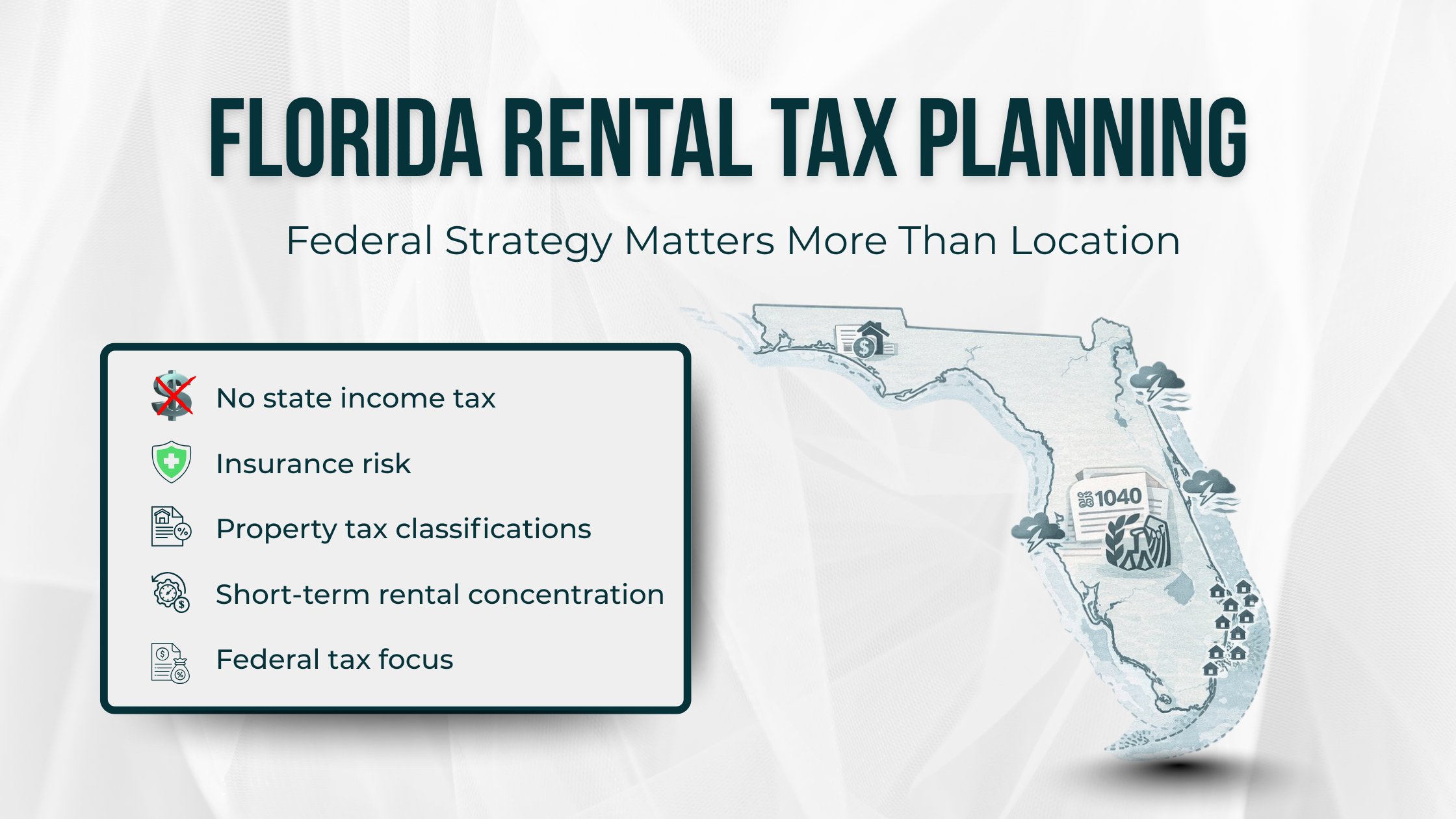

Florida-Specific Considerations That Matter

Florida’s lack of a state income tax shifts the focus entirely to federal planning.

Property taxes, homestead rules, and insurance costs carry more weight. Short-term rentals face greater scrutiny in certain markets, increasing operational risk.

From a tax perspective, Florida investors benefit most from disciplined federal optimization, asset protection planning, and long-term sequencing rather than state-level arbitrage.

Homestead benefits generally do not apply to rental properties and may be compromised if a property is converted to rental use.

Short-Term vs Long-Term Rentals as Part of a Broader Plan

The real decision is not short-term versus long-term. It is how the asset fits into a ten-year plan.

That includes income timing, depreciation strategy, entity design, retirement coordination, and exit planning.

At Square, we view rental real estate as one component of a larger tax architecture, not a standalone tactic.

Conclusion

Short-term and long-term rentals both have a place in sophisticated tax planning. But they serve different roles.

Short-term rentals emphasize timing and active classification. Long-term rentals emphasize durability and exit efficiency.

The right choice depends on income trajectory, liquidity needs, risk tolerance, and long-term objectives. When structured intentionally, either strategy can support wealth accumulation. When chosen casually, both can disappoint.

The difference is planning.

Designed for high-income investors and business owners planning beyond deductions.

Frequently Asked Questions: Short-Term vs Long-Term Rental Tax Strategy

Are short-term rentals taxed differently than long-term rentals?

Yes, and the difference is structural, not cosmetic. Short-term rentals can qualify as an active trade or business if specific participation and stay-length tests are met. That classification can allow losses to offset wages or business income. Long-term rentals are generally passive by default, meaning losses are typically limited to passive income unless special planning applies. Over a decade, this classification difference drives materially different tax outcomes.

Is a short-term rental considered a business for tax purposes?

It can be. A short-term rental may be treated as a business when average guest stays are sufficiently short and the owner materially participates. When that threshold is met, income and losses are not automatically passive. However, business treatment also brings added complexity around recordkeeping, entity structure, and exit planning. Business classification should be chosen deliberately, not assumed.

Which rental strategy provides better tax benefits over time?

Neither strategy is inherently better. Short-term rentals often produce stronger front-loaded tax benefits through accelerated depreciation and active loss treatment. Long-term rentals tend to produce more durable, predictable outcomes with fewer exit complications. The better strategy depends on income trajectory, liquidity needs, risk tolerance, and planned holding period. Over a ten-year horizon, sustainability often matters more than year-one savings.

Can cost segregation be used for both short-term and long-term rentals?

Yes, but it should not be used the same way. For short-term rentals, cost segregation often amplifies early losses that can offset active income. For long-term rentals, aggressive acceleration can reduce long-term efficiency and increase recapture exposure. Cost segregation should support a broader multi-year plan, not function as a standalone tactic.

Do short-term rental losses offset W-2 or business income?

They can, but only when the rental qualifies as non-passive and the owner meets material participation requirements. Many investors assume this treatment applies automatically. It does not. Failure to meet participation thresholds can convert expected deductions into suspended losses, undermining the intended strategy.

How does depreciation recapture differ between short-term and long-term rentals?

The mechanics are the same, but the impact is different. Short-term rental strategies often accelerate more depreciation early, increasing potential recapture at sale. Long-term rentals usually spread depreciation more evenly, which can result in smoother exit outcomes. Recapture should be modeled upfront, especially when accelerated depreciation is part of the plan.

Does Florida’s lack of state income tax change the rental tax strategy?

Yes. Florida’s no state income tax environment places greater emphasis on federal tax optimization, timing, and asset protection rather than state-level arbitrage. Decisions around depreciation, entity structure, and exit planning tend to matter more in Florida than in high-tax states where state deductions drive part of the analysis.

Should rental strategy be decided before or after buying the property?

Before. Rental classification, entity structure, financing, and depreciation strategy are most effective when decided prior to acquisition. Retroactive fixes are limited and often expensive. High-income investors benefit most when the rental strategy is designed as part of a broader, multi-year tax plan rather than after the first return is filed.