Cost Segregation as a Timing Tool, Not a One-Time Tax Play

High-income Florida taxpayers rarely struggle with understanding deductions. The real challenge is timing. When income peaks, cash flow tightens, exits approach, or estate plans evolve, the question is not what deductions are available, but when they should be used and what they disrupt later.

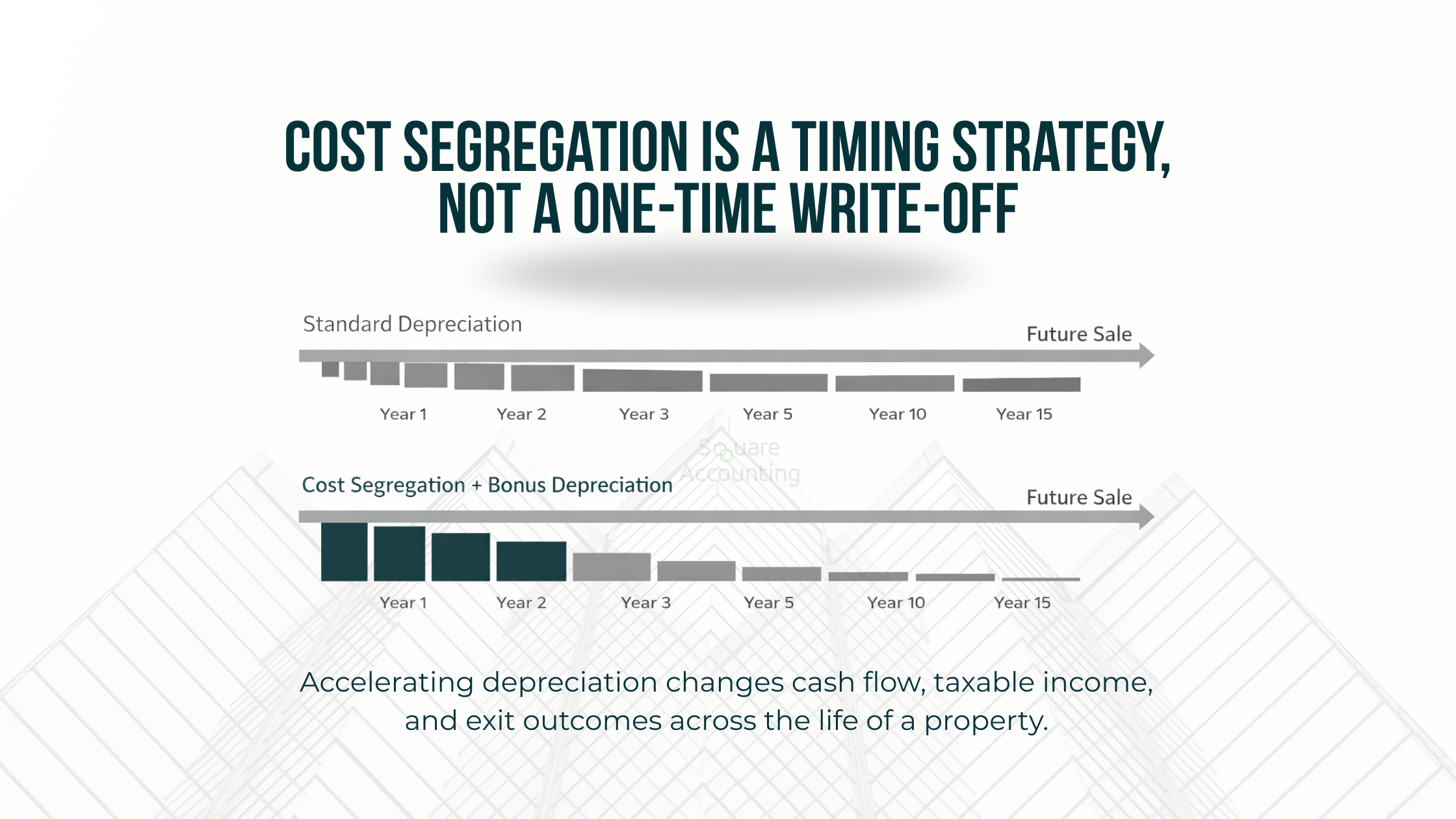

Cost segregation sits squarely in that conversation. Too often, it is treated as a one-time acceleration tactic instead of what it really is: a multi-year timing tool that reshapes taxable income, cash flow, and exit economics over the life of an asset.

For real estate investors, business owners, and professionals earning $250k+ annually, the value of cost segregation depends less on the study itself and more on how it fits into a broader planning sequence.

This article explains how we think about cost segregation at Square Accounting: not as a write-off, but as a lever that must be pulled deliberately.

Key Takeaways

Cost segregation is about income timing, not permanent tax elimination

The real risk is not missing depreciation, but using it at the wrong stage of your income cycle

Bonus depreciation magnifies short-term benefit while increasing future exposure to recapture and rate risk

Entity structure and passive activity rules often determine whether cost segregation creates value or friction

Florida’s no state income tax environment makes federal timing and exit planning more critical, not less

If you’re considering cost segregation, the real question is timing. A short strategy review helps determine whether acceleration improves your long-term tax position or simply shifts the problem forward.

Cost Segregation Is an Asset-Based Timing Strategy

Most articles frame cost segregation as a way to “increase deductions.” That misses the point.

Cost segregation is fundamentally about recharacterizing the depreciation timeline of a property. By identifying components that qualify for shorter recovery periods, depreciation is pulled forward into earlier years.

That shift has consequences:

Higher deductions now

Lower depreciation later

A changed tax profile at sale or refinance

This is not good or bad in isolation. It is only effective when aligned with:

Peak earning years

Planned liquidity events

Changes in marginal tax rates

Estate and succession goals

Used correctly, cost segregation smooths tax exposure across decades. Used casually, it front-loads relief while creating future friction.

Bonus Depreciation: Amplifier, Not the Strategy

Bonus depreciation often drives interest in cost segregation, but it should never be the starting point.

2025 bonus depreciation reality check (federal): Under current law, 100% bonus depreciation is available again for most qualified property acquired and placed in service after January 19, 2025. There are transitional rules for assets placed in service earlier in January 2025, and taxpayers may have elections that affect how the percentage applies.

Why this matters: the planning question is no longer only “how fast is bonus phasing out?” It’s “should we use 100% now, or deliberately temper acceleration to preserve deductions for later years?”

Recent bonus percentages (context):

80% (2023),

60% (2024), and the phase-down would have reached

40% (2025),

20% (2026),

0% (2027+)

but 2025 legislation reinstated 100% for most qualified property after Jan 19, 2025.

Bonus depreciation simply accelerates what cost segregation already reclassifies. The combined effect can produce large upfront deductions, but it also:

Compresses depreciation into fewer years

Increases future taxable income

Raises the stakes on recapture

For high earners, the question is not whether bonus depreciation is available. It is whether today’s marginal rate is meaningfully higher than tomorrow’s.

If income is temporarily elevated due to:

A liquidity event

Business wind-down

One-time professional income spike

Acceleration may make sense. If income is expected to remain stable or grow, pulling depreciation forward can reduce long-term flexibility.

Cash Flow vs. Tax Savings: The Real Trade-Off

Cost segregation is often sold as a cash flow enhancer. In practice, it is a cash flow reshaper.

Short-term benefits:

Reduced federal tax payments

Increased after-tax cash in early years

Long-term trade-offs:

Higher taxable income later

Reduced shelter during stabilization or downturn years

Greater exposure at sale

Sophisticated planning weighs whether early cash flow will be reinvested productively or merely consumed. Without reinvestment discipline, timing advantages fade quickly.

Active vs. Passive Treatment Drives Outcomes

For Florida real estate investors, the difference between active and passive classification often determines whether cost segregation is powerful or wasted.

If losses are suspended, cost segregation can still be valuable, but the timing benefit may shift from ‘current-year tax reduction’ to ‘future release planning’ at disposition. That changes how we evaluate the holding period, the expected gain profile, and whether exit is taxable, exchanged, or transferred through an estate plan.

If losses are passive and suspended, acceleration offers little immediate benefit. Those losses may only unlock upon sale, at which point:

Recapture applies

Capital stack decisions matter

Estate strategies intersect

Cost segregation should be coordinated with:

Real estate professional status planning

Grouping elections

Spousal participation strategies

Absent that coordination, depreciation timing can misalign with usability.

Entity Structure and Ownership Matter More Than the Study

LLCs, partnerships, S corporations, and trusts all interact differently with accelerated depreciation.

Key considerations include:

Allocation of losses among partners

Basis limitations

Exit mechanics

Transfer and estate implications

Cost segregation executed before entity restructuring can lock in inefficiencies. Executed after thoughtful structuring, it becomes a precision tool.

This is where most do-it-yourself or study-first approaches fall apart.

Exit, Recapture, and Long-Term Sustainability

Depreciation does not disappear. It reappears later.

At exit, cost segregation often increases §1245 depreciation recapture exposure (generally ordinary-income recapture) because more basis has been allocated to shorter-lived personal property. Meanwhile, building-related depreciation is governed by §1250 rules, which can produce different rate treatment for individuals. The point is not that recapture eliminates the benefit, but that the mix of §1245 vs. §1250 changes the exit economics and should be modeled.

What Most Articles Get Wrong

Most cost segregation content fails high earners in three ways:

Overemphasis on upfront savings without modeling downstream effects

Ignoring ownership and income timing, assuming deductions are always usable

Treating cost segregation as a yes/no decision, rather than a sequencing decision

Common mistakes we see:

Running studies immediately after purchase without income context

Pairing cost segregation with bonus depreciation reflexively

Ignoring how future refinancing or sale plans change the math

There are also situations where cost segregation may not be appropriate, including:

Properties intended for near-term sale

Investors with limited passive income absorption

Assets owned in misaligned entities

Many high earners implement cost segregation before modeling income cycles, entity structure, or exit plans. We review those factors first, then decide if the strategy fits.

Florida-Specific Considerations That Change the Analysis

Florida’s lack of state income tax shifts the cost segregation conversation almost entirely to federal timing and exit planning.

For investors, most holdings are non-homestead, so property tax increases and reassessment dynamics tend to hit harder than they do for owner-occupied homestead properties—making after-tax cash flow modeling more sensitive to insurance and operating cost volatility.

Additional Florida-specific factors include:

High real estate concentration among local investors

Short-term rental volatility and income swings

Insurance and casualty considerations affecting holding periods

Property tax differences between homestead and non-homestead assets

Without state tax arbitrage, the value of acceleration depends even more on federal rate management and long-term planning discipline.

Conclusion: Timing Is the Strategy

Cost segregation is not a loophole. It is not a one-time play. And it is not universally beneficial.

For high-income Florida taxpayers, it is a timing instrument that must be integrated with income forecasting, entity design, exit planning, and reinvestment strategy.

When approached as part of a multi-year plan, cost segregation can meaningfully improve after-tax outcomes. When approached tactically, it often shifts tax pain rather than reducing it.

At Square Accounting, we evaluate cost segregation the same way we evaluate any advanced tax tool: by asking how it fits into the full arc of a client’s financial life.

Cost segregation works best when it’s part of a multi-year plan. If you want clarity on whether and when it makes sense, we’re happy to walk through the numbers.

Frequently Asked Questions About Cost Segregation (Strategic Focus)

Is cost segregation worth it for high-income taxpayers?

Cost segregation can be worth it for high-income taxpayers, but only when it aligns with income timing, ownership structure, and long-term plans. The strategy creates value by accelerating depreciation into higher tax-rate years. If income is stable, declining, or losses cannot be currently used, the benefit may be delayed or reduced. For sophisticated taxpayers, the decision is less about eligibility and more about sequencing.

Is cost segregation a one-time tax deduction?

No. Cost segregation is not a one-time deduction. It is a depreciation reclassification strategy that shifts deductions forward in time. While it can create large upfront deductions, it also reduces depreciation in later years and increases exposure to depreciation recapture upon sale. Treating it as a one-time tax play often leads to poor long-term outcomes.

How does cost segregation affect depreciation recapture?

Cost segregation increases depreciation recapture because more depreciation is taken earlier in the asset’s life. At sale, portions of the accelerated depreciation are typically recaptured at ordinary income tax rates rather than capital gains rates. This does not eliminate the benefit, but it makes exit planning and holding period analysis critical.

Should cost segregation always be combined with bonus depreciation?

No. Bonus depreciation amplifies cost segregation, but it should not be applied automatically. Bonus depreciation accelerates deductions even further, which can be beneficial in peak income years but problematic if future tax rates increase or income declines. High earners should evaluate whether current marginal tax rates justify the long-term trade-offs.

Can cost segregation create losses I cannot use?

Yes. If depreciation losses are passive and you do not have sufficient passive income or qualifying active status, losses may be suspended. Those losses are carried forward and often only realized upon sale, at which point recapture and rate considerations apply. This is why passive activity rules must be addressed before implementing cost segregation.

Does cost segregation make sense for Florida investors without state income tax?

Florida’s lack of state income tax makes federal timing more important, not less. Without state-level savings, the value of cost segregation depends entirely on federal rate arbitrage, income volatility, and exit planning. Florida investors must be especially disciplined about modeling long-term outcomes rather than focusing solely on upfront savings.

When is the best time to do a cost segregation study?

The best time to do a cost segregation study is when taxable income is high and expected to be meaningfully lower in the future, or when depreciation can be reinvested productively. Studies performed immediately after acquisition without considering income cycles, entity structure, or exit plans often underperform.

Does cost segregation affect refinancing or future sales?

Yes. Accelerated depreciation can complicate forecasting and lender presentation, depending on lender add-back policies and how pro forma cash flow is prepared. At sale, cost segregation increases depreciation recapture and can change after-tax proceeds. These effects should be modeled before implementing the strategy, not after.

Is cost segregation appropriate for short-term rental properties?

It can be, but short-term rentals introduce income volatility, active versus passive classification issues, and holding period uncertainty. Cost segregation works best when income usability and long-term ownership strategy are clearly defined. Without that clarity, acceleration can create more complexity than value.

What is the biggest mistake investors make with cost segregation?

The most common mistake is treating cost segregation as a standalone tax deduction rather than a long-term planning tool. Failing to coordinate it with income timing, entity structure, bonus depreciation decisions, and exit strategy often shifts taxes rather than reducing them.