Who Owns the Asset, Who Gets the Deduction, and Why It Changes Everything

For high-income Florida taxpayers, the biggest tax mistakes are rarely about missing a deduction. They’re about placing the deduction in the wrong hands, at the wrong time, inside the wrong structure.

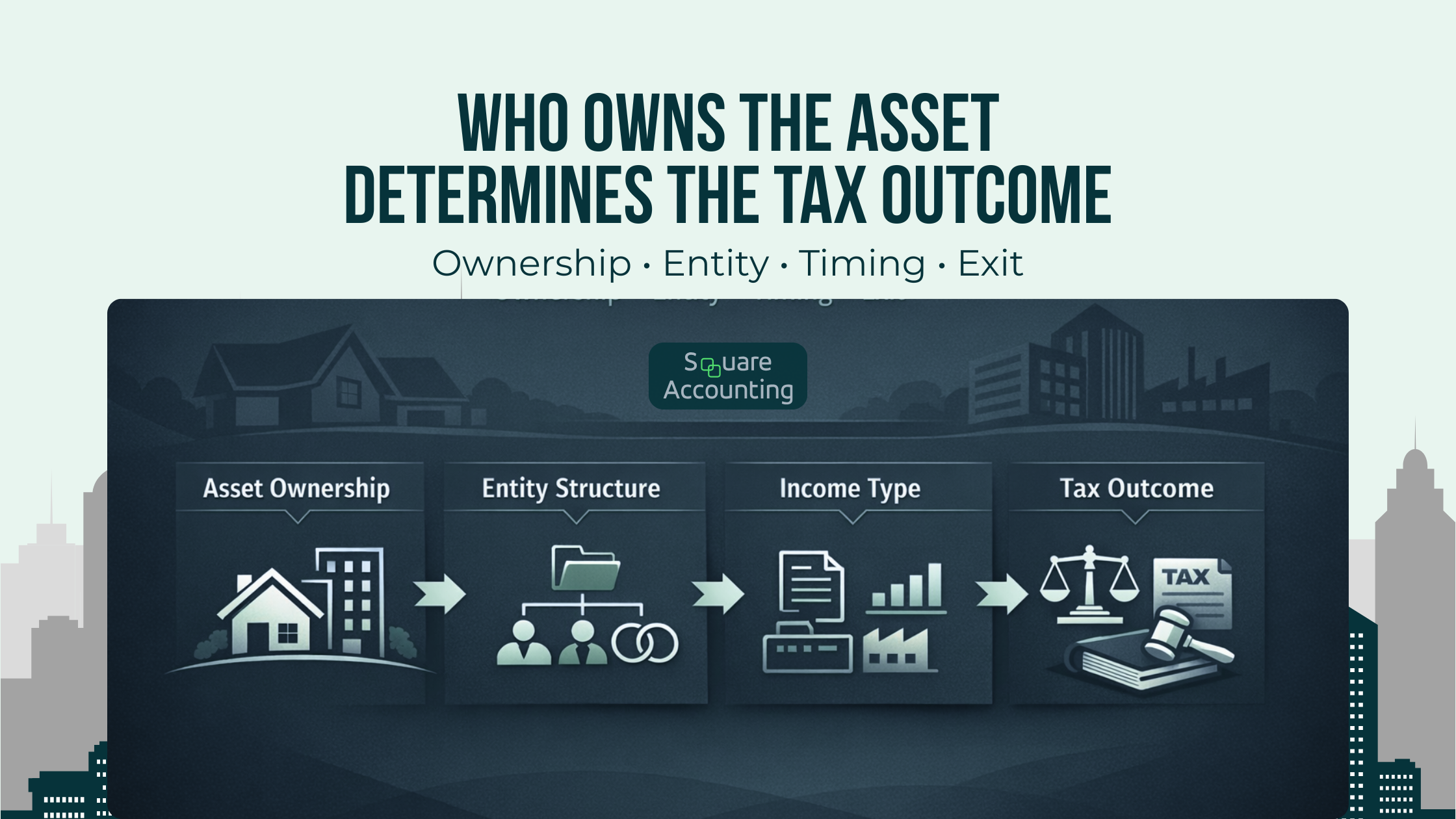

At higher income levels, tax planning stops being transactional. The question is no longer “Is this deductible?” It’s who owns the asset, who is entitled to the deduction, how that deduction interacts with income classification, and what happens over the next 10, 20, or 30 years.

This distinction matters more in Florida than most states. With no state income tax, federal tax exposure becomes the dominant variable. Real estate holdings are often concentrated. Entity structures are layered. Exit planning, asset protection, and estate considerations are already in motion.

Ownership is not a legal footnote. It is the control panel for depreciation, losses, credits, recapture, and long-term ROI. Get it right and deductions compound into durable tax efficiency. Get it wrong and you create stranded losses, unusable depreciation, or expensive surprises at exit.

This article explains why ownership determines deductions, how that flows through multi-year planning, and where sophisticated taxpayers routinely misstep.

Key Takeaways

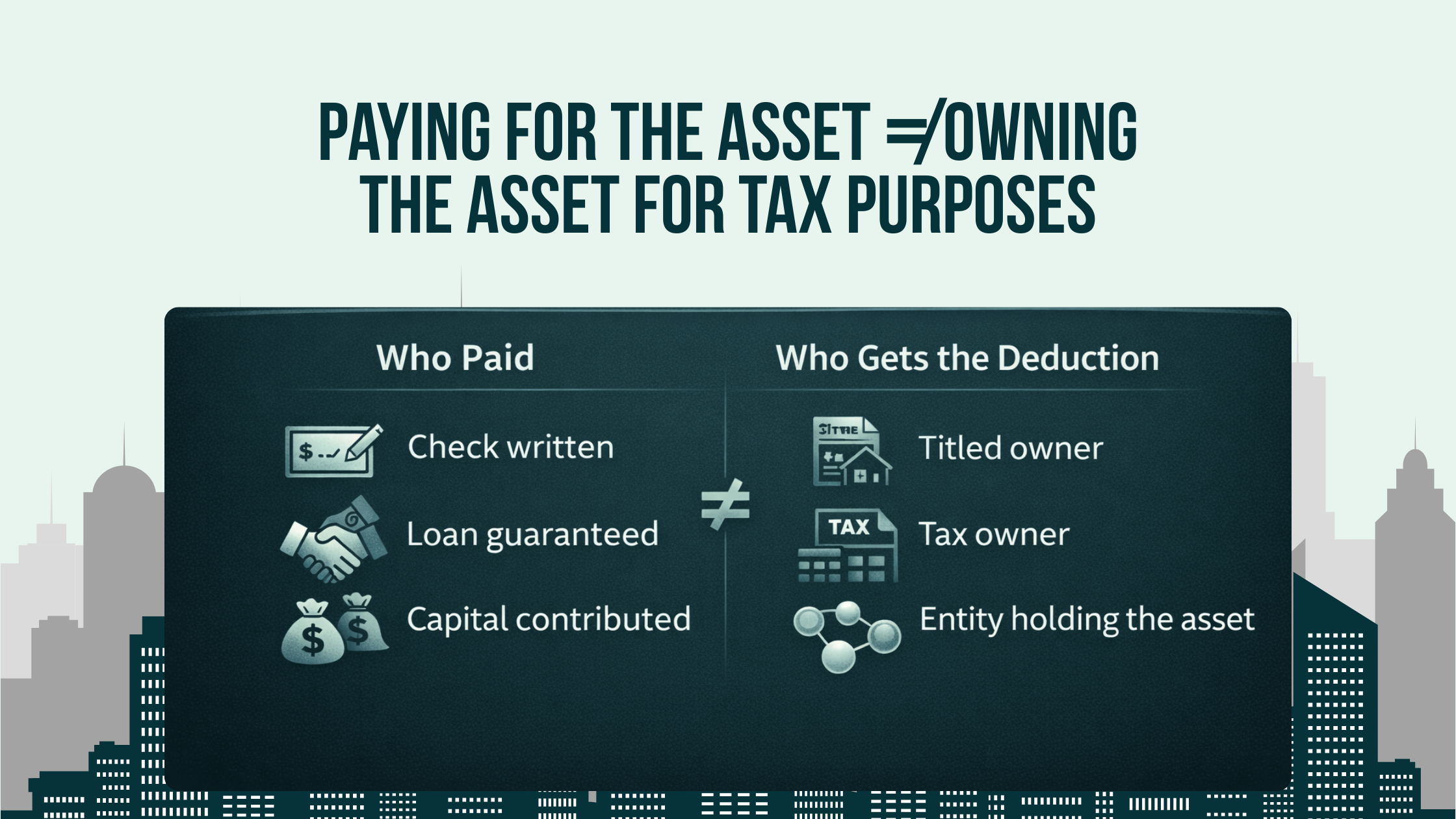

Deductions follow ownership, not payment. Who writes the check is irrelevant if they don’t own the asset for tax purposes.

Entity structure determines usability. Depreciation in the wrong entity can become trapped by passive loss rules or income mismatch.

Timing and sequencing matter more than magnitude. Accelerated deductions without future modeling often create recapture and exit friction.

Asset-based planning beats deduction chasing. Long-term ROI depends on how assets perform inside the broader tax system.

Florida’s tax environment magnifies structural errors. With no state income tax, federal inefficiencies are harder to offset.

Exit is where most strategies fail. If ownership wasn’t designed with disposition in mind, today’s deductions become tomorrow’s tax bill.

If your deductions feel unpredictable or underutilized, the issue is often ownership—not income. A focused review can identify whether your current structures are working as intended.

The Core Principle: Deductions Follow Ownership

Tax law is consistent on one foundational point: the taxpayer who owns the asset is the taxpayer entitled to the deduction.

Deductions generally follow the tax owner of the asset, not simply the party who funded the purchase. Paying the bill can matter in specific contexts (for example, reimbursement arrangements or capital contributions), but depreciation and most property-level deductions track the taxpayer treated as the owner for federal tax purposes.

Ownership is not defined by:

Who paid for the asset

Who guarantees the loan

Who benefits economically in an informal sense

Ownership is defined by:

Title and beneficial ownership

Entity classification

Risk of loss and right to income

This distinction becomes critical when assets are held across:

Multiple LLCs

Partnerships and S corporations

Trusts or estate structures

Operating companies and real estate holding companies

If depreciation, interest, or operating losses land in an entity that cannot use them efficiently, the deduction may be technically valid but strategically useless.

Entity Structure Is the Delivery System for Tax Benefits

High earners often assume deductions are universally beneficial. They’re not. Deductions only matter if they offset the right type of income in the right place.

One sequencing point sophisticated investors sometimes overlook: at-risk limitations apply before passive activity limitations when determining whether losses are currently deductible. That ordering affects how much loss is allowed, how it’s characterized, and what carries forward into future years.

Active vs Passive Income Mismatch

Real estate depreciation is typically passive. Business income may be active. W-2 income is neither.

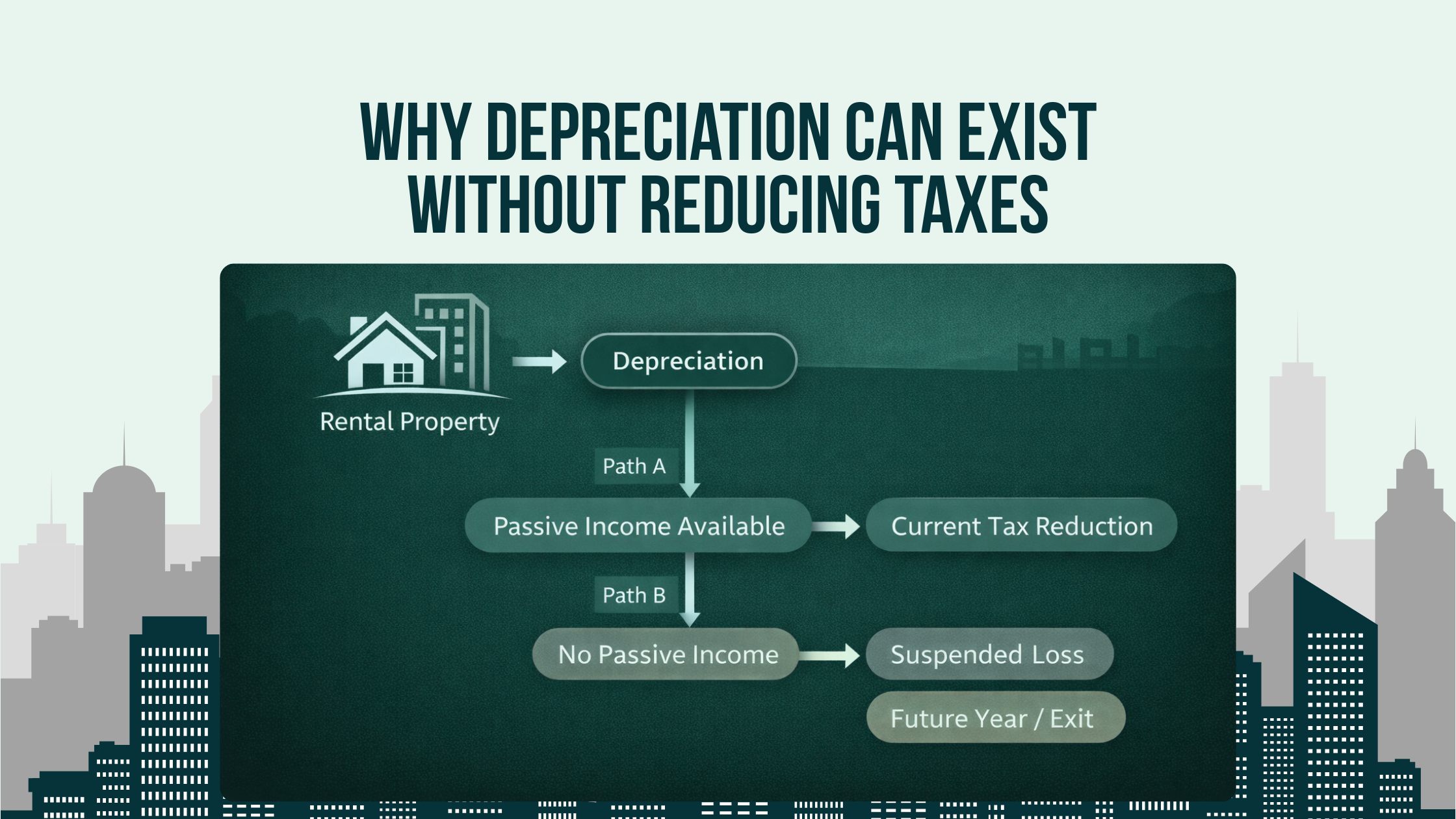

If:

A property is owned by a passive entity

The taxpayer does not qualify as a real estate professional

There is no passive income to absorb losses

Then depreciation accumulates but does not reduce current tax liability.

These “paper losses” are deferred, not eliminated. They sit idle until:

They sit idle until there is sufficient passive income or you dispose of your entire interest in the activity in a taxable disposition, which generally allows previously disallowed passive losses from that activity to be deducted in that year.

This is not inherently bad. But it must be intentional.

S Corporations and the Wrong Kind of Ownership

We routinely see real estate placed into S corporations for perceived simplicity. Often, that structure creates avoidable constraints (basis and distribution mechanics, limited flexibility for capital allocations, and exit complications). There are narrow situations where an S corporation can be workable, but for many depreciable real estate holdings, partnerships or disregarded entities provide cleaner long-term planning flexibility.

S corporations:

Restrict loss utilization

Complicate basis calculations

Create issues with distributions and exit

Convert otherwise flexible depreciation into rigid structures

The asset still depreciates. The problem is where the depreciation goes and how it can be used.

Asset-Based Tax Planning vs Deduction-Driven Thinking

Most articles frame depreciation, bonus depreciation, or cost segregation as tactics. That’s a mistake.

Sophisticated planning starts with the asset itself:

What income does it generate?

How stable is that income?

How long will it be held?

How will it be exited or transferred?

For residential rental real estate, the baseline federal depreciation framework generally assumes a 27.5-year recovery period under MACRS for the building (excluding land), with cost segregation potentially reclassifying components into shorter-lived property where supported.

Only then do we determine:

Ownership structure

Entity placement

Depreciation strategy

Timing of acceleration

Cost Segregation as a Planning Tool, Not a Shortcut

Cost segregation can be powerful. It front-loads depreciation. But front-loading deductions without modeling future years is short-sighted. Bonus depreciation also remains a moving variable. Under current federal rules, the special depreciation allowance is phased down, and for many types of qualified property placed in service in 2025 the general percentage is 40% (with different percentages applying in certain specialized cases). That makes modeling even more important, because the same cost segregation study can produce meaningfully different outcomes depending on when the asset is placed in service.

Questions that matter more than “How much can we accelerate?”:

Will the losses be usable now?

Will they create suspended losses?

How will recapture be handled at exit?

Does the asset’s holding period justify acceleration?

For Florida investors with long-term holds, aggressive acceleration may reduce flexibility later when income changes, entities shift, or exit timing evolves.

Cash Flow vs Tax Savings: A Trade-Off, Not a Binary Choice

Ownership affects not just taxes, but cash flow.

Example:

A high-income business owner personally guarantees debt on a property held in a partnership.

The partnership generates depreciation but limited cash distributions.

The deductions are passive and unusable today.

Result:

Cash flow services debt

Tax benefits are deferred

Liquidity planning becomes strained

This isn’t wrong. But it must align with:

Liquidity needs

Income trajectory

Long-term investment goals

Tax efficiency that impairs cash flow is not efficient.

Timing and Sequencing: Where Sophisticated Planning Lives

The most overlooked variable in ownership planning is when deductions show up relative to income events.

Key sequencing considerations:

Acquiring assets before or after liquidity events

Aligning depreciation with peak earning years

Coordinating with business exits or equity vesting

Planning around retirement transitions

Ownership determines whether deductions hit during:

High marginal tax years

Low-income transition periods

Post-exit years when income mix changes

A deduction taken in the wrong year is not neutral. It’s wasted potential.

Timing errors don’t show up on this year’s return. They show up over the next decade. Multi-year modeling helps align deductions, income, and exit strategy before the window closes.

Exit, Recapture, and the Long View

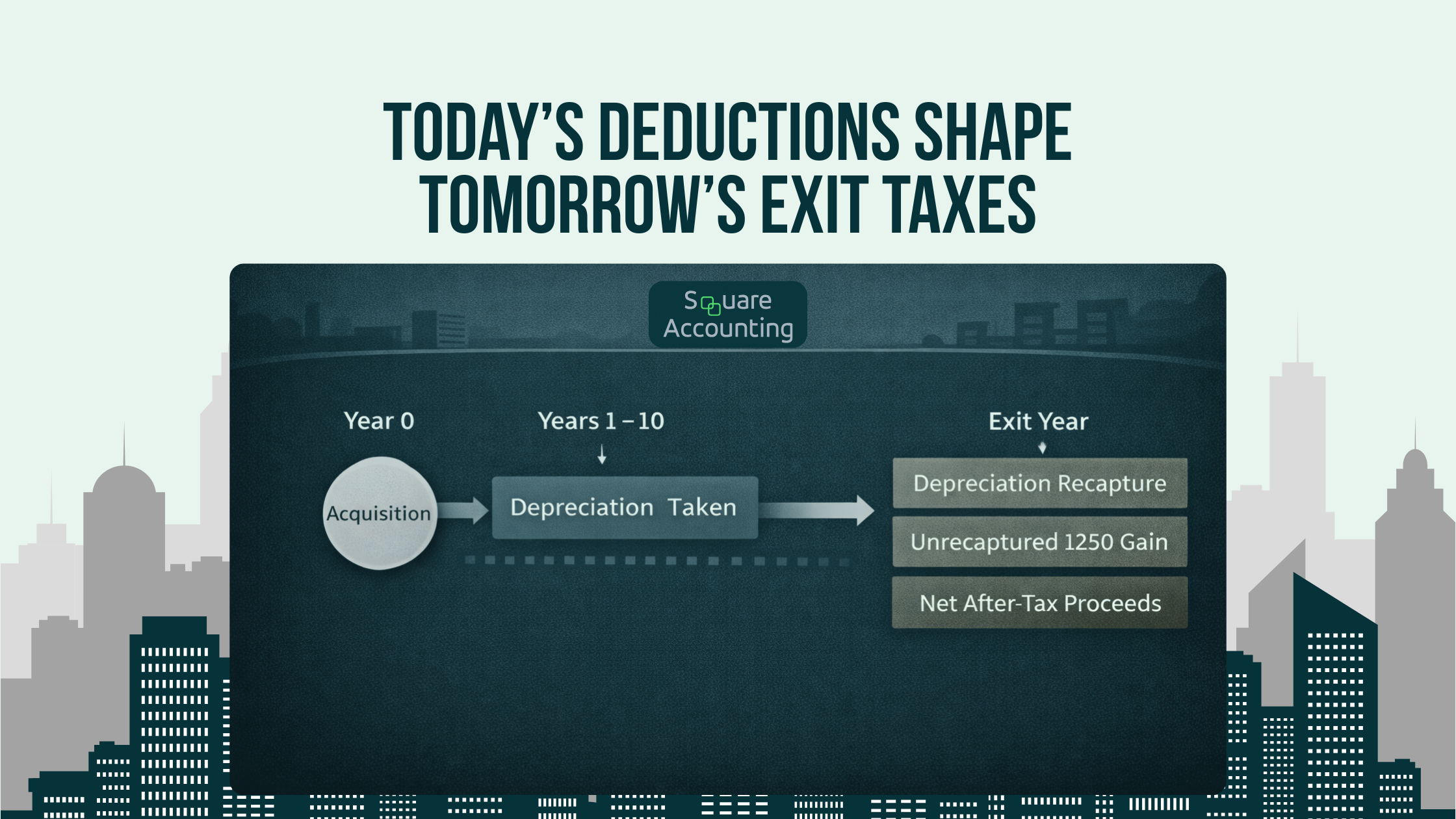

Depreciation is not free money. It is a timing mechanism.

At exit:

Accelerated depreciation increases recapture exposure

Ownership structure determines tax character

Poor planning can shift part of the economics of a sale into less favorable tax buckets. Depending on the asset type, depreciation may be recaptured as ordinary income (for example, many types of personal property under Section 1245), while depreciation on real property is commonly reflected as unrecaptured Section 1250 gain, taxed at up to 25%.

Common errors include:

Ignoring depreciation recapture until sale

Holding assets in entities that complicate 1031 exchanges

Misaligning ownership with estate planning goals

The best ownership structures are designed backwards from exit, not forwards from acquisition.

What Most Articles Get Wrong (Or Leave Out)

Most content on this topic oversimplifies to the point of being misleading.

Common Oversights

Assuming deductions are universally good

Not all deductions reduce tax today. Some defer it. Some misplace it.Ignoring income classification

Passive losses do not offset active income without qualification.Treating entity choice as administrative

Entity structure is a tax strategy, not a filing preference.Skipping exit modeling

Recapture and disposition planning are often afterthoughts.Overusing acceleration

Front-loading deductions without long-term projections often backfires.

When the Strategy Requires Caution

Ownership-driven deduction strategies may not work well when:

Income is volatile

Liquidity is constrained

Exit timing is uncertain

Entities are already overly complex

Estate plans are unresolved

Complexity should serve strategy, not replace it.

Florida-Specific Planning Considerations

Florida changes the math in subtle but important ways.

No State Income Tax Cuts Both Ways

Without a state income tax:

Federal deductions carry more weight

There’s no state offset if deductions are misallocated

Timing errors are harder to unwind

Real Estate Concentration Risk

Many Florida taxpayers hold:

Large portions of net worth in real estate

Short-term or mixed-use rental properties

Assets exposed to insurance and climate risks

Ownership structures must account for:

Risk segregation

Casualty planning

Flexibility to restructure if insurance markets shift

Homestead vs Non-Homestead Implications

Primary residences, rental properties, and investment real estate behave differently under:

Property tax regimes

Creditor protection

Estate planning rules

Ownership decisions often bleed into non-tax consequences that still affect long-term outcomes.

Conclusion: Ownership Is the Strategy

At higher income levels, tax efficiency is no longer about finding deductions. It’s about placing assets correctly so deductions work when and where they matter most.

Ownership determines:

Who gets the deduction

When it can be used

How it interacts with income

What happens at exit

In Florida’s tax environment, these decisions are amplified. There’s less margin for error and more upside for precision.

At Square Accounting, we view ownership not as a legal formality, but as a strategic lever. The right structure doesn’t just reduce tax this year. It supports income flexibility, preserves optionality, and aligns tax outcomes with long-term goals.

The question isn’t whether a deduction exists. It’s whether it exists in the right place, at the right time, for the right reason.

Effective tax planning isn’t about finding deductions. It’s about placing assets correctly over time. A structured consultation can determine whether your current ownership, entities, and income sources are aligned.

Frequently Asked Questions: Asset Ownership and Tax Deductions

Who gets the tax deduction when an asset is purchased?

The tax deduction goes to the taxpayer or entity that owns the asset for tax purposes, not the person who paid for it or guaranteed the loan.

Ownership is determined by legal and beneficial ownership, including who has the right to income and bears the risk of loss. If an LLC or partnership owns the asset, the deduction flows through according to the ownership structure and tax classification of that entity.

This is why placing assets in the wrong entity can result in deductions that exist on paper but provide little or no tax benefit.

Does the person who pays for the asset get the deduction?

No. Paying for an asset does not determine who gets the deduction.

A common planning mistake occurs when one party funds the purchase while another entity holds title. For tax purposes, deductions such as depreciation, interest, and operating expenses follow ownership, not cash flow.

This distinction is especially important in family structures, related-party transactions, and multi-entity real estate portfolios.

How does asset ownership affect depreciation deductions?

Depreciation is allocated to the tax owner of the asset, and its usefulness depends on:

The owner’s income classification (active vs passive)

The entity type

Available income to absorb the deduction

If depreciation is generated in a passive entity with no passive income, the deduction may be suspended and carried forward rather than reducing current tax liability. Ownership determines not only who claims depreciation, but whether it can be used strategically.

Can depreciation be deducted if the asset is owned by an LLC?

Yes, but the tax treatment depends on how the LLC is classified.

A single-member LLC is typically disregarded for tax purposes, and deductions flow directly to the owner.

A multi-member LLC taxed as a partnership passes deductions through to members based on the operating agreement.

An LLC taxed as an S corporation introduces additional limitations and is often a poor vehicle for holding depreciable real estate.

The LLC itself does not eliminate tax friction. Structure and classification matter more than the label.

Why do passive loss rules prevent me from using my deductions?

Passive loss rules limit the ability to offset passive losses against active or portfolio income.

If you do not qualify as a real estate professional and do not materially participate, losses from rental real estate generally cannot offset:

W-2 income

Active business income

Investment income

These losses are not lost, but they are deferred until there is passive income or the asset is disposed of. Ownership structure determines whether this limitation is a temporary planning choice or a long-term inefficiency.

Is it better to own assets personally or through an entity?

There is no universal answer. The correct ownership depends on:

Income type and level

Liability exposure

Long-term hold vs exit plans

Estate and succession goals

Ability to use deductions efficiently

For high-income taxpayers, entity ownership often improves risk management and planning flexibility, but it can also create deduction traps if not designed correctly. The question is not simplicity versus complexity, but alignment.

How does ownership affect tax outcomes when the asset is sold?

Ownership determines:

Who recognizes the gain

Whether depreciation recapture applies

The character of income (ordinary vs capital)

Eligibility for deferral strategies such as exchanges

Accelerated depreciation taken earlier increases recapture exposure at sale. If the ownership structure was not designed with exit in mind, today’s deductions can significantly increase tomorrow’s tax liability.

Does Florida’s no state income tax change how deductions work?

Florida’s lack of state income tax does not change federal deduction rules, but it raises the stakes of federal planning.

Because there is no state offset:

Federal deductions carry more weight

Misallocated or unusable deductions are harder to compensate for

Timing errors have a larger long-term impact

Ownership decisions that might be partially offset in high-tax states become more consequential in Florida.

Can cost segregation deductions be wasted?

Yes. Cost segregation can generate large depreciation deductions, but they can be strategically wasted if:

The owner cannot use passive losses

The deductions occur in low-income years

Exit and recapture are not modeled in advance

Cost segregation should be applied as part of a multi-year ownership and income strategy, not as a stand-alone tactic.

What is the biggest mistake high-income earners make with asset ownership?

The most common mistake is treating deductions as isolated benefits instead of system-wide outcomes.

High earners often focus on whether a deduction exists rather than:

Where it lands

When it can be used

How it interacts with income classification

What it does to future flexibility and exit taxes

At advanced income levels, ownership is not a formality. It is the mechanism that determines whether tax benefits compound or quietly erode long-term wealth.