Structuring LLCs, Partnerships, and S-Corps for Long-Term Tax Control

For high-income Florida taxpayers, the tax problem is rarely that income is undertaxed. It is that income is poorly structured.

Most business owners and real estate investors earning $250,000 or more already pursue deductions aggressively. They accelerate depreciation where available. They make retirement contributions. Yet over a decade, their effective tax rate remains stubbornly high, and their tax outcomes feel increasingly rigid.

Most readers in this position already operate through multiple entities, hold real estate alongside operating income, and sense that their advisors are optimizing in isolation rather than as a coordinated system.

The root issue is not missed tactics. It is structural drift. Entities are formed at different times, for different reasons, without a unified view of how income, assets, and exits will interact over multiple tax years.

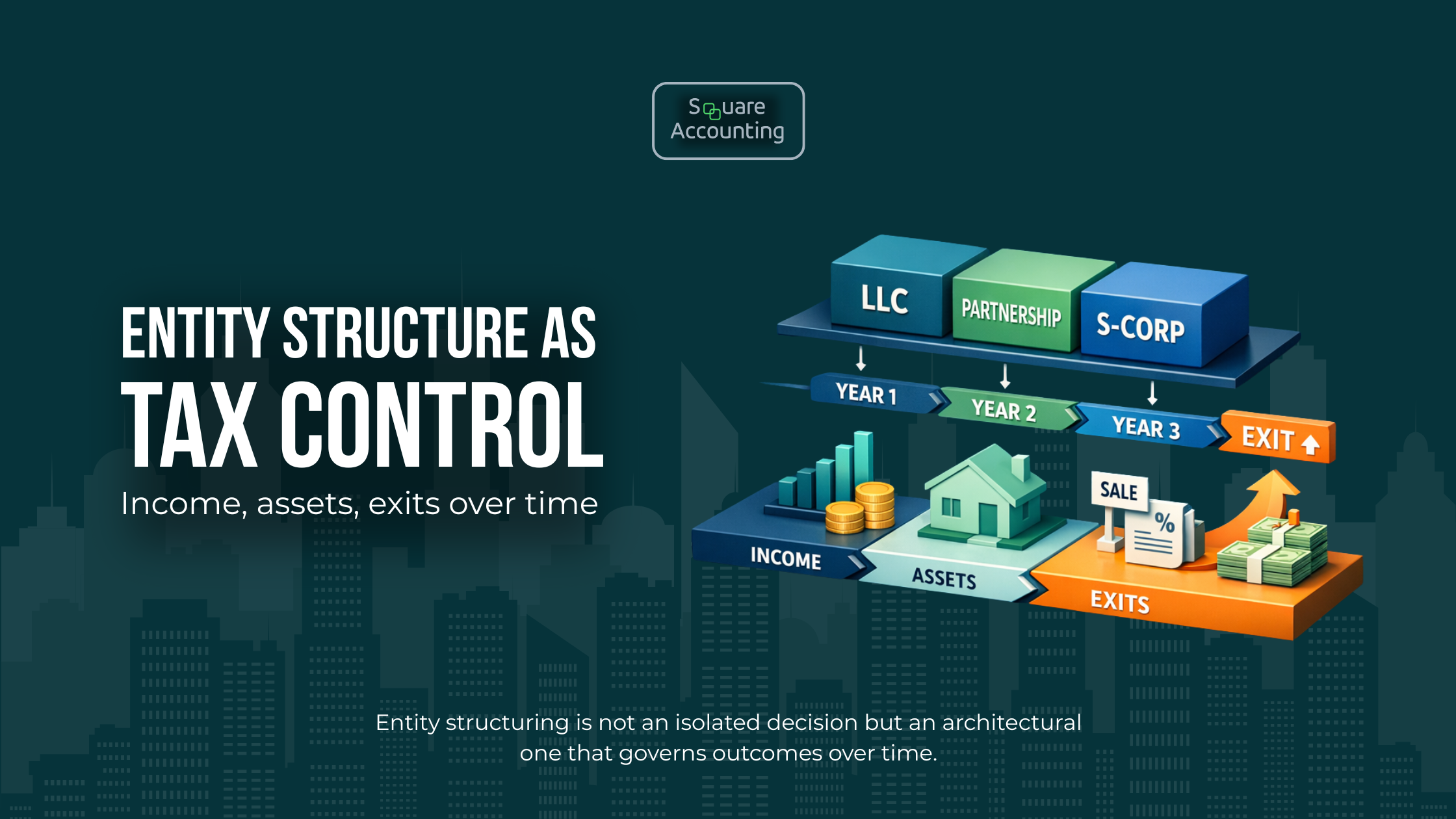

Entity structuring is not an administrative decision. It is a long-term tax control system. When designed deliberately, LLCs, partnerships, and S-corps determine not just how much tax is paid this year, but how income is classified, how losses are absorbed, how capital is recovered, and how exits are taxed over an entire career or investing lifetime.

Key Takeaways

Entity structure governs income character, loss usability, and exit taxation over decades, not just annually

LLCs, partnerships, and S-corps create fundamentally different long-term constraints and opportunities

Timing and sequencing of elections, acquisitions, and ownership changes often matter more than the strategy itself

Depreciation and cost segregation shift tax across time and owners; they do not eliminate it

Over-optimizing for short-term tax savings can increase recapture, reduce cash flow, and erode flexibility

Florida’s no state income tax environment amplifies federal structural decisions

We help evaluate whether your current entity structure supports passive versus active income alignment over multiple tax years.

Entity Structure as a Long-Term Tax Control System

Entity choice is often framed as a threshold decision made at formation. In reality, it is a control system that operates across the full lifecycle of income generation, asset accumulation, and exit.

Each entity structure answers a different set of questions:

Who is taxed on the income, and how is it characterized

When losses can be used, and by whom

Whether payroll taxes apply and to what extent

How capital is returned, refinanced, or redeployed

What happens when assets are sold, transferred, or inherited

For high earners, marginal tax rates are already elevated. The planning objective shifts from minimizing tax in isolation to managing when, how, and on whom tax is imposed over time.

The LLC as a Planning Container, Not a Strategy

An LLC is not a tax strategy. It is a legal container that becomes meaningful only once its tax classification, ownership design, and asset purpose are defined.

In Florida, LLCs are frequently used to isolate liability in real estate portfolios. From a tax perspective, their value lies in optionality. An LLC can be disregarded, taxed as a partnership, or taxed as an S-corp. Each path carries long-term consequences.

Using LLCs interchangeably for operating businesses, rental real estate, and investment holding entities often results in:

Mismatched income and loss profiles

Trapped passive losses

Inflexible exit outcomes

The LLC itself provides no tax advantage. The planning advantage comes from intentionally pairing the LLC’s tax treatment with the asset and the owner’s role.

Partnership Taxation and Capital Alignment Over Time

Partnership taxation remains the most flexible framework available for sophisticated investors, particularly where capital, labor, and risk are not evenly distributed.

When structured correctly, partnerships allow:

Allocation of depreciation and losses to owners who can use them

Capital account tracking that preserves economic intent across refinances and exits

Distribution mechanics that separate tax allocation from cash flow

This flexibility is critical for high-income real estate investors combining active operators with passive capital or mixing operating businesses with asset ownership.

However, flexibility without discipline creates long-term problems. Poorly designed allocation provisions often surface during refinancing or sale, when depreciation recapture and capital gains must be allocated consistently with historical capital accounts.

A structured review can reveal how today’s entity choices affect depreciation use, loss timing, and long-term exit flexibility.

S-Corps: Payroll Tax Control Versus Structural Rigidity

S-corps are frequently positioned as tax-saving vehicles due to payroll tax reduction. That benefit is real but incomplete.

An S-corp exchanges flexibility for payroll tax control. For stable service businesses with predictable income, that trade-off can be appropriate. For asset-heavy businesses or evolving investment structures, it can become constraining.

Limitations include:

Mandatory reasonable compensation rules

Inability to allocate income or loss disproportionately

Reduced compatibility with real estate and depreciation-heavy assets

Limited flexibility during ownership transitions

In Florida, where there is no state income tax, payroll tax savings can dominate early analysis. Over time, those payroll tax savings may be offset by reduced allocation and exit flexibility, depending on how the business and assets evolve.

Asset-Based Tax Planning Versus Deduction Chasing

High earners often evaluate tax strategies based on visible deductions. Asset-based planning focuses instead on income origination and character.

Entity structure determines whether:

Income is earned, passive, or portfolio

Losses offset operating income or remain suspended

Depreciation creates usable shelter or deferred friction

Capital events trigger favorable or punitive tax treatment

For investors with real estate, operating businesses, and professional income, aligning depreciation capacity with active income sources is often the difference between sustainable tax control and deferred frustration.

Active Versus Passive Treatment as a Structural Outcome

Passive activity rules are not a compliance footnote. They are a long-term planning constraint.

Entity design influences whether losses:

Offset high-rate operating income

Are deferred indefinitely

Are released only upon disposition

Misalignment leads to growing pools of suspended losses that appear valuable but functionally inaccessible, often neutralized by depreciation recapture at exit.

Cost Segregation and Depreciation as Timing Tools

Accelerated depreciation is frequently applied without modeling long-term consequences. This is one of the most common structural failures among high-income taxpayers.

Cost segregation accelerates deductions into earlier years. It does not remove tax from the system. Entity structure determines who benefits now and who bears the burden later.

Long-term planning requires evaluating:

Expected holding period

Likelihood of refinancing versus sale

Ability of specific owners to absorb losses

Impact of recapture on future liquidity

When depreciation is layered into the wrong entity or ownership profile, it concentrates tax risk rather than diffusing it.

Cash Flow Versus Tax Efficiency Trade-Offs

Tax efficiency does not always improve economic outcomes.

Certain structures reduce tax at the expense of:

Distributable cash

Borrowing capacity

Reinvestment flexibility

Examples include excessive salary minimization that restricts distributions or aggressive depreciation that impairs refinancing. Sustainable planning weighs tax savings against long-term capital velocity.

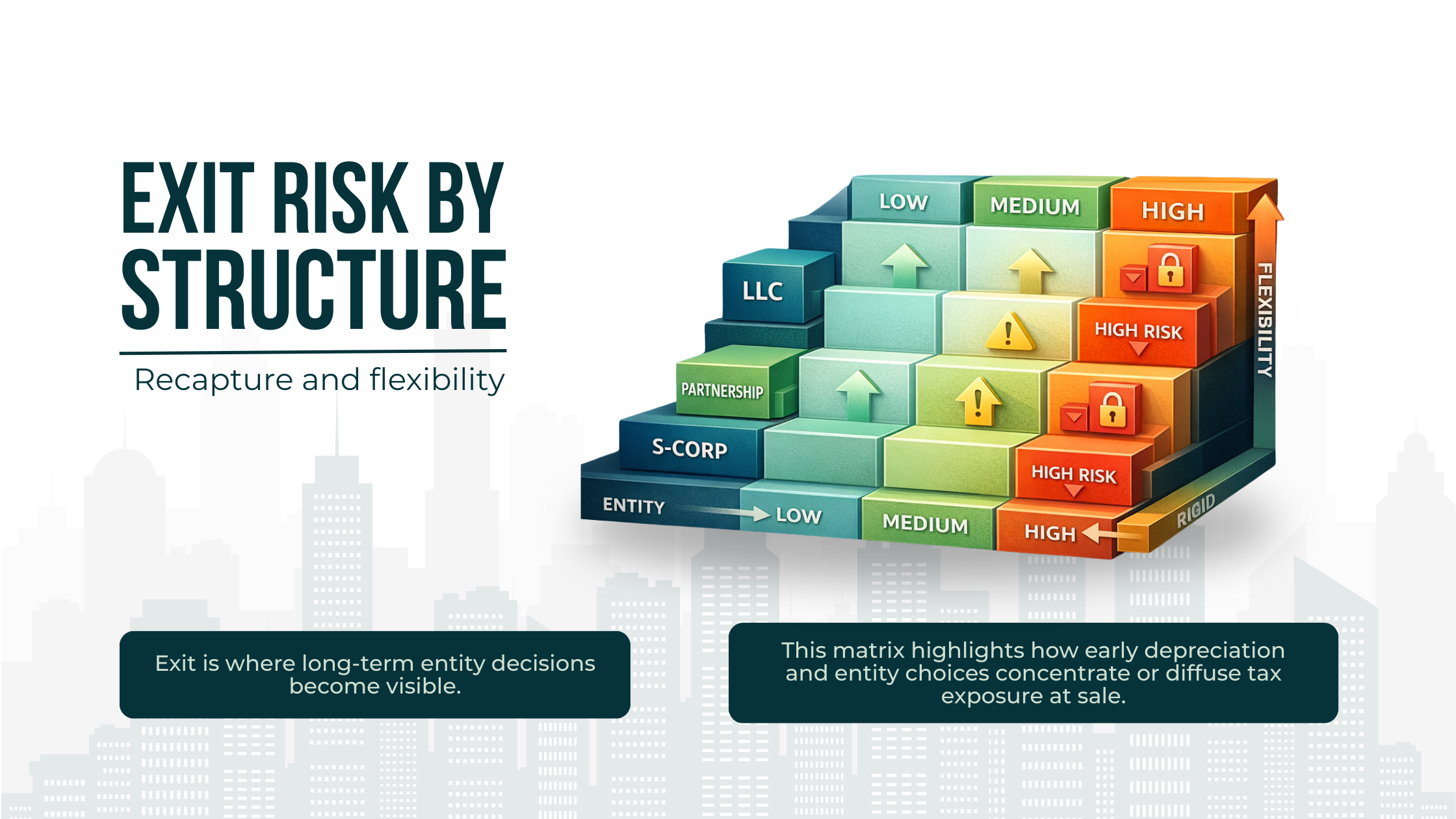

Exit Planning, Recapture, and Structural Durability

Exit is where entity design reveals its quality.

Entity structure affects:

Ordinary income versus capital gain treatment

Allocation of depreciation recapture

Ability to reposition or roll capital

Transferability to heirs or successors

In Florida, where federal tax dominates, exit planning is not optional. Decisions made years earlier determine whether a sale creates flexibility or friction.

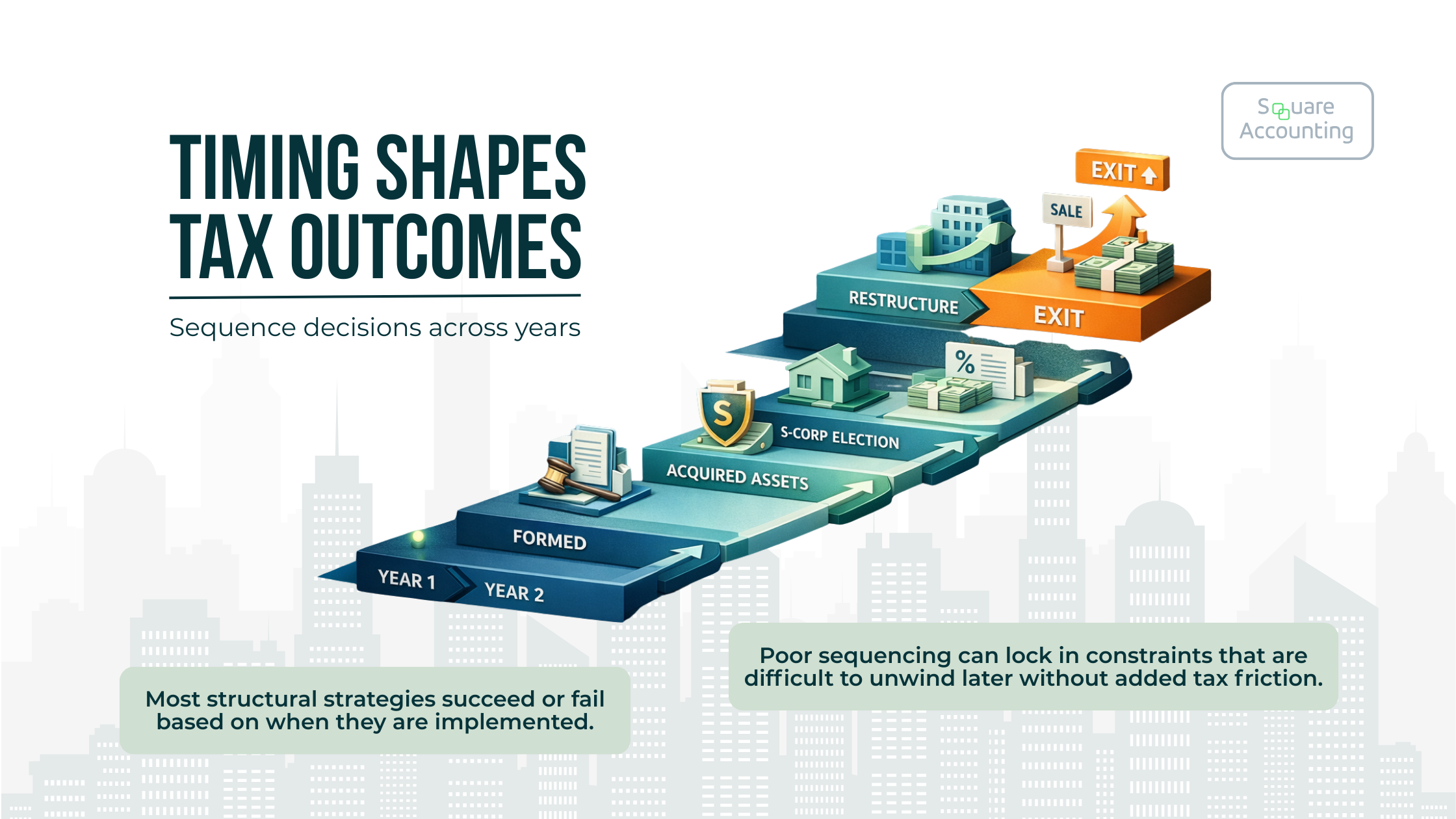

Timing and Sequencing Across Multiple Tax Years

Most strategies fail not because they are flawed, but because they are mistimed.

Common sequencing errors include:

Electing S-corp status before income stabilizes

Acquiring depreciable assets in entities without loss absorption capacity

Changing ownership without aligning capital accounts

Triggering exits before suspended losses can be released

Multi-year planning requires deliberate sequencing so each decision supports the next.

Correcting Common Misuse and Oversights

Even sophisticated taxpayers often fall into structural traps:

Treating S-corps as universal solutions

Segmenting LLCs without tax coordination

Using partnerships without disciplined allocation mechanics

Accelerating depreciation without exit modeling

Allowing advisors to optimize independently rather than collaboratively

These issues compound quietly and surface when flexibility is gone.

We assess how your LLCs, partnerships, and S-corps interact across years so sequencing decisions and recapture exposure are addressed intentionally.

Florida-Specific Structural Considerations

Florida’s lack of state income tax amplifies federal planning decisions. There is no secondary tax system to offset structural mistakes.

Additional considerations include:

High real estate concentration and property tax classifications

Homestead versus non-homestead cash flow implications

Insurance and casualty risks influencing entity separation

Short-term rental activity affecting income characterization

In this environment, entity structure becomes the primary lever for lifetime tax control.

Conclusion

LLCs, partnerships, and S-corps are not interchangeable tools. They are long-term frameworks that shape how income, losses, and capital behave across decades.

For high-income Florida taxpayers, effective planning requires coordination. Entity structure must align with asset type, income profile, investor role, and exit intent. Timing and sequencing matter as much as the strategy itself.

Sustainable tax control is not achieved through one-off deductions or isolated elections. It is built through deliberate, multi-year structural design that preserves flexibility and supports informed decision-making over time.

Structural decisions often intersect with geography, particularly in states where federal outcomes dominate.

We review entity structure through a multi-year lens to identify where income classification, depreciation, and exit planning diverge.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does the timing of an S-corp election affect long-term tax outcomes?

S-corp elections tend to work best when income is stable and the role of the owner is unlikely to change materially. Electing too early can lock in payroll tax mechanics before cash flow, ownership, or asset mix has settled. Over time, this can limit flexibility around distributions, capital raises, or adding depreciable assets. Sequencing matters because reversing or restructuring later often introduces friction that offsets early payroll tax savings.

When should entity restructuring be considered, and when does it create more risk than value?

Restructuring is most effective when driven by forward-looking changes: new assets, shifts in activity level, or a defined exit horizon. It tends to create risk when done reactively in response to a single high-income year. Late-stage restructures can disrupt capital accounts, trigger unintended income recognition, or reduce loss usability. Timing restructures around transitions, rather than tax spikes, generally produces more durable outcomes.

How does depreciation recapture influence entity choice over a long holding period?

Depreciation recapture is often manageable in early years but becomes decisive at exit. Entity structure determines how recapture is allocated, whether it offsets other income, and who bears the burden. Over a long holding period, aggressive depreciation in the wrong entity can convert apparent tax deferral into concentrated ordinary income. Evaluating recapture exposure alongside entity choice helps prevent deferred tax from becoming a liquidity problem later.

Can an entity structure that works well today create problems at exit?

Yes. Structures optimized for current income or loss utilization can produce friction during sale or transfer. Common issues include mismatched capital accounts, limited ability to reallocate gains, or restrictions on ownership changes. What feels efficient during accumulation may reduce flexibility when assets are sold or repositioned. Exit modeling during entity design helps balance near-term benefits against long-term constraints.

How do ownership percentages and roles affect long-term tax efficiency?

Ownership design influences far more than profit sharing. It affects who absorbs losses, who recognizes income, and how gains are allocated at exit. In partnerships, ownership roles can be aligned with capital and activity, but only if allocations are structured intentionally. In more rigid entities, ownership changes can have disproportionate tax effects. Aligning ownership with long-term economic intent helps preserve flexibility as circumstances evolve.

Why does Florida’s lack of state income tax change entity planning priorities?

Without state income tax, federal outcomes carry more weight. There is less room to offset structural inefficiencies. For Florida investors, this places greater emphasis on income classification, depreciation timing, and exit planning at the federal level. Real estate concentration, property tax distinctions, insurance exposure, and short-term rental activity further elevate the importance of getting entity structure right from the start.

How should insurance and casualty risk factor into entity structure decisions?

Insurance and casualty considerations often influence how assets are segmented across entities. While liability protection is the primary driver, tax implications follow. Separating assets can affect loss utilization, depreciation aggregation, and future exits. In Florida, where casualty exposure is a real planning factor, entity separation should balance risk management with long-term tax efficiency rather than treating each concern in isolation.